Jan Janszoon van Haarlem, commonly known as

Murat Reis the Younger (c. 1570 – c. 1641), was a

Dutch pirate in Morocco who

converted to Islam after being captured by a Moorish state in 1618. He began serving as a pirate, one of the most famous of the 17th-century "

Salé Rovers". Together with other

corsairs, he helped establish the independent

Republic of Salé at the city of that name, serving as the first President and Grand Admiral. He also served as Governor of

Oualidia.

| Military service | |

|---|

| Personal details | |

|---|

| Governor of Oualidia | |

|---|

| Governor of Salé (ceremonial) | |

|---|

| Grand Admiral of Salé | |

|---|

| Jan Janszoon | |

|---|

| |

In office

1619–1627 | |

In office

1623–1627 | |

| Appointed by | Sultan Zidan Abu Maali |

|---|

In office

1640–1641 | |

| Appointed by | Sultan Mohammed esh Sheikh es Seghir |

|---|

| Born | Jan Janszoon van Salee / Van Haarlem

c. 1570

Haarlem, County of Holland |

|---|

| Died | 1641 or later

Morocco |

|---|

| Nationality | Dutch, Moroccan |

|---|

| Children | Lysbeth Janszoon van Haarlem, Anthony Janszoon van Salee, Abraham Janszoon van Salee, Philip Janszoon van Salee, Cornelis Janszoon van Salee |

|---|

| Occupation | Admiral |

|---|

| Allegiance | Morocco |

|---|

| Rank | Grand Admiral (Reis) |

|---|

Early lifeEdit

Jan Janszoon van Haerlem was born in

Haarlem in 1575, which was in

Holland, then a province ruled by the

Habsburg Monarchy. The

Eighty Years War between Dutch rebels and the

Spanish Empire under King Philip II had started seven years before his birth; it lasted all his life. Little is known of his early life. He married Soutgen Cave in 1595 and had two children with her, Edward and Lysbeth.

After her death, around 1600 he married or had a union with Margarita, a

Moorish woman in

Cartagena, Spain. They had four sons together: Abraham, Anthony, Phillip, and Cornelis.

Anthony went on to be one of the first European settlers of

New Amsterdam.

PrivateeringEdit

In 1600, Jan Janszoon began as a Dutch

privateer sailing from his home port of

Haarlem, working for the state with letters of marque to harass Spanish shipping during the Eighty Years' War. Janszoon overstepped the boundaries of his letters and found his way to the semi-independent port states of the

Barbary Coast of north Africa, whence he could attack ships of every foreign state: when he attacked a Spanish ship, he flew the Dutch flag; when he attacked any other, he became an Ottoman Captain and flew the red half-moon of the Turks or the flag of any of various other Mediterranean principalities. During this period, he had abandoned his Dutch family.

[1]

Capture by Barbary corsairsEdit

Sail

Sail plan for a

Polacca, first built by the Barbary pirates around the 16th century, many scholars believe the

Polacca was extensively used by Jan Janszoon. The ship could sail with a large crew of 75 and was armed with 24

cannons.

Janszoon was captured in 1618 at

Lanzarote (one of the

Canary Islands) by

Barbary corsairs and taken to

Algiers as a captive. There he "turned Turk", or

Muslim. Some historians speculate that the conversion was forced.

[2] Janszoon himself, however, tried very hard to convert his fellow Europeans who were Christian to become Muslim and was a passionate Muslim missionary.

[3] The Ottoman Turks maintained a precarious measure of influence on behalf of their

Sultan by openly encouraging the

Moors to advance themselves through piracy against the European powers, which long resented the Ottoman Empire. After Janszoon's conversion to

Islam and the ways of his captors, he sailed with the famous corsair Sulayman Rais, also known as Slemen Reis. (He was a Dutchman named

De Veenboer,

[4] whom Janszoon had known before his capture and who,

[5] had chosen to convert to Islam). They were accompanied by

Simon de Danser.[

citation needed] But, because

Algiers had concluded peace with several European nations, it was no longer a suitable port from which to sell captured ships or their cargo. So, after Sulayman Rais was killed by a cannonball in 1619, Janszoon moved to the ancient port of

Salé and began operating from it as a

Barbary corsair.

Republic of SaléEdit

Salé

Salé in the 1600s

Main article:

Republic of Salé

In 1619,

Salé Rovers declared the port to be an independent republic free from the Sultan. They set up a government that consisted of 14 pirate leaders and elected Janszoon as their President. He would also serve as the Grand Admiral, known as Murat Reis, of their navy.

[6] The Salé fleet totaled about eighteen ships, all small because of the very shallow harbor entrance.

After an unsuccessful siege of the city, the Sultan of Morocco acknowledged its semi-autonomy. Contrary to popular belief that Sultan

Zidan Abu Maali had reclaimed sovereignty over Salé and appointed Janszoon the Governor in 1624, the Sultan acknowledged Janszoon's election as president by formally appointing him as his ceremonial governor.

[7]

The walls of

Marrakesh and

El Badi Palace, by

Adriaen Matham, 1640.

Under Janszoon's leadership, business in Salé thrived. The main sources of income of this republic remained piracy and its by-trades, shipping and dealing in stolen property. Historians have noted Janszoon's intelligence and bravery, which were expressed in his leadership ability. He was forced to find an assistant to keep up, resulting in the hiring of a fellow countryman from The Netherlands, Mathys van Bostel Oosterlinck, who would serve as his Vice-Admiral.

[8]

Janszoon had become very wealthy from his income as pirate admiral, payments for anchorage and other harbor dues, and the brokerage of stolen goods. The political climate in Salé worsened toward the end of 1627, so Janszoon quietly moved his family and his entire operation back to semi-independent Algiers.

Plea from his Dutch familyEdit

Janszoon became bored by his new official duties from time to time and again sail away on a pirate adventure. In 1622, Janszoon and his crews sailed into the

English Channel with no particular plan but to try their luck there. When they ran low on supplies, they docked at the port of

Veere,

Zeeland, under the Moroccan flag, claiming diplomatic privileges from his official role as Admiral of Morocco (a very loose term in the environment of North African politics). The Dutch authorities could not deny the two ships access to Veere because, at the time, several peace treaties and trade agreements existed between the Sultan of Morocco and the

Dutch Republic. During Janszoon's anchorage there, the Dutch authorities brought his Dutch first wife and children to the port to try to persuade him to give up piracy. Such strategies utterly failed with the men.

[9] Janszoon and his crews left port with many new Dutch volunteers, despite a Dutch prohibition of piracy.

DiplomacyEdit

Dutch captivesEdit

While in Morocco, Janszoon worked to secure release of Dutch captives from other pirates and prevent their being sold into slavery.

[10]

Franco-Moroccan Treaty of 1631Edit

Knowledgeable of several languages, while in Algiers he contributed to the establishment of the

Franco-Moroccan Treaty of 1631 between

French King Louis XIII and Sultan

Abu Marwan Abd al-Malik II.

[10]

Notable raidsEdit

Ólafur Egilsson

Ólafur Egilsson was captured by Murat Reis the Younger

LundyEdit

In 1627 Janszoon captured the island of

Lundy in the

Bristol Channel and held it for five years, using it as a base for raiding expeditions.

[11]

IcelandEdit

In 1627, Janszoon used a

Danish "slave" (most likely a crew member captured on a Danish ship taken as a pirate prize) to pilot him and his men to

Iceland. There they raided the fishing village of

Grindavík. Their takings were meagre, some salted fish and a few hides, but they also captured twelve Icelanders and three Danes who happened to be in the village. When they were leaving Grindavík, they managed to trick and capture a Danish merchant ship that was passing by means of flying a false flag.[

citation needed]

The ships sailed to

Bessastaðir, seat of the Danish governor of Iceland, to raid but were unable to make a landing – it is said they were thwarted by cannon fire from the local fortifications (

Bessastaðaskans) and a quickly mustered group of

lancers from the

Southern Peninsula.

[12] They decided to sail home to Salé, where they sold their captives as slaves.

Two corsair ships from Algiers, possibly connected to Janszoon's raid, came to Iceland on July 4 and plundered there. Then they sailed to Vestmannaeyjar off the southern coast and raided there for three days. Those events are collectively known in Iceland as

Tyrkjaránið (the

Turkish abductions), as the Barbary states were nominally a part of the Ottoman Empire.

[13]

Accounts by enslaved Icelanders who spent time on the corsair ships claimed that the conditions for women and children were normal, in that they were permitted to move throughout the ship, except to the quarter deck. The pirates were seen giving extra food to the children from their own private stashes. A woman who gave birth on board a ship was treated with dignity, being afforded privacy and clothing by the pirates. The men were put in the hold of the ships and had their chains removed once the ships were far enough from land. Despite popular claims about treatment of captives, Icelander accounts do not mention that slaves were raped on the voyage itself,

[14] however,

Guðríður Símonardóttir, one of the few captives to later return to Iceland, was sold into sex slavery as a concubine.

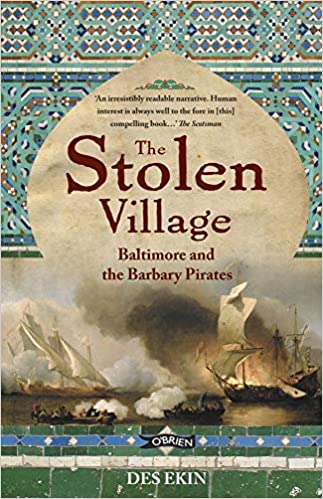

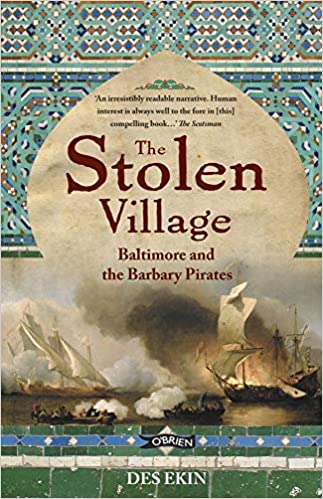

Sack of Baltimore, IrelandEdit

Having sailed for two months and with little to show for the voyage, Janszoon turned to a captive taken on the voyage, a

Roman Catholic named John Hackett, for information on where a profitable raid could be made. The Protestant residents of Baltimore, a small town in

West Cork, Ireland, were resented by the Roman Catholic native Irish because they were

settled on lands confiscated from the O'Driscoll clan. Hackett directed Janszoon to this town and away from his own. Janszoon

sacked Baltimore on June 20, 1631, seizing little property but taking 108 captives, whom he sold as slaves in North Africa. Janszoon was said to have released the Irish and taken only English captives. Shortly after the sack, Hackett was arrested and hanged for his crime. "Here was not a single Christian who was not weeping and who was not full of sadness at the sight of so many honest maidens and so many good women abandoned to the brutality of these barbarians".

[15] Only two of the villagers ever returned to their homeland.

[16]

Raids in the Mediterranean SeaEdit

Murat Reis chose to make large profits by raiding Mediterranean islands such as the

Balearic Islands,

Corsica,

Sardinia, and the southern coast of

Sicily. He often sold most of his merchandise in

Tunis, where he befriended the

Dey. He is known to have sailed the

Ionian Sea. He fought the Venetians near the coasts of

Crete and

Cyprus with a corsair crew consisting of

Dutch,

Moriscos,

Arab,

Turkish and elite

Janissaries.

Capture by Knights of MaltaEdit

Fort Saint Angelo

Fort Saint Angelo in

Valletta,

Malta

In 1635, near the

Tunisian coast, Murat Reis was outnumbered and surprised by a sudden attack. He and many of his men were captured by the

Knights of Malta. He was imprisoned in the island's notorious dark

dungeons. He was mistreated and

tortured, and suffered ill health due to his time in the dungeon. In 1640 he barely escaped after a massive Corsair attack, which was carefully planned by the

Dey of

Tunis in order to rescue their fellow sailors and Corsairs. He was greatly honored and praised upon his return in Morocco and the nearby

Barbary States.

Escape and return to MoroccoEdit

After Janzsoon returned to Morocco in 1640, he was appointed as Governor of the great fortress of

Oualidia, near

Safi. He resided at the Castle of Maladia. In December 1640, a ship arrived with a new Dutch consul, who brought Lysbeth Janszoon van Haarlem, Janszoon's daughter by his Dutch wife, to visit her father. When Lysbeth arrived, Janszoon "was seated in great pomp on a carpet, with silk cushions, the servants all around him".

[17] She saw that Murat Reis had become a feeble, old man. Lysbeth stayed with her father until August 1641, when she returned to Holland. Little is known of Janszoon thereafter; he likely retired at last from both public life and piracy. The date of his death remains unknown.

Marriages and issueEdit

In 1596, by an unknown Dutch woman, Janszoon's first child was born, Lysbeth Janszoon van Haarlem.

After becoming a privateer, Janszoon met an unknown woman in

Cartagena, Spain, who he would marry. The identity of this woman is historically vague, but the consensus is that she was of multi-ethnic background, considered "Moorish" in Spain. Historians have claimed her to be nothing more than a concubine, others claim she was a Muslim

Mudéjar who worked for a Christian noble family, and other claims have been made that she was a "Moorish princess."

[18] Through this marriage, Janszoon had four children: Abraham Janszoon van Salee (b.1602), Philip Janszoon van Salee (b. 1604),

Anthony Janszoon van Salee (b.1607), and Cornelis Janszoon van Salee (b. 1608).

It is speculated that Janszoon married for a third time to the daughter of

Sultan Moulay Ziden in 1624.

[10]

Popular cultureEdit

In 2009, a play based on Janszoon's life as a pirate, "Jan Janszoon, de blonde Arabier", written by

Karim El Guennouni toured The Netherlands.

[19] "Bad Grandpa: The Ballad of Murad the Captain" is a children's poem about Janszoon published in 2007.

[20]

NamesEdit

Janszoon was also known as

Murat Reis the Younger. His Dutch names are also given as

Jan Jansen and

Jan Jansz; his adopted name as

Morat Rais,

Murat Rais,

Morat;

Little John Ward,

John Barber,

Captain John,

Caid Morato were some of his pirate names. "The Hairdresser" was a nickname of Janszoon.

[10]

See alsoEdit

NotesEdit

- ^ Karg and Spaite (2007): 36

- ^ "Murad Rais", Pirate Utopias, p. 96, Retrieved 29 Sept 2009.

- ^ Stephen Snelders, The Devil's Anarchy: The Sea Robberies of the Most Famous Pirate Claes G. Compaen, p. 24, After his conversion, Jansz. proselytized actively for his new faith, trying to convert Christian slaves...

- ^ "De Veenboer", Zeerovery, Retrieved 29 Sept 2009.

- ^ "Murad Reis", p. 36

- ^ "Murad Reis", Pirate Utopias, p. 97, Retrieved 30 September 2009.

- ^ "Murad Rais", p.98

- ^ "Murad Rais", p. 98

- ^ "Murad Rais", p.99

- ^ a b c d "VAN SICKELEN & VAN HOORN LINES continued" Archived 2011-10-01 at the Wayback Machine, Michael A. Shoemaker. PCEZ. Accessed 9 september 2011

- ^ Konstam, Angus (2008). Piracy: The Complete History. Osprey Publishing. pp. 90–91. ISBN 1-84603-240-7. Retrieved 2011-04-29.

- ^ Vilhjálmur Þ. Gíslason, Bessastaðir: Þættir úr sögu höfuðbóls. Akureyri. 1947.

- ^ The Travels of Reverend Ólafur Egilsson. Archived 2014-01-06 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "Murad Rais", p. 129

- ^ Ekin, Des (2006). The Stolen Village. OBrien. p. 177. ISBN 978-0-86278-955-8.

- ^ "Murad Rais", p. 121, 129

- ^ "Murad Rais", p.140

- ^ "Anthony Jansen van Salee", Pirate Utopias, p. 206, Retrieved 29 sept 2009.

- ^ "Jan Janszoon knipoogt naar het heden", 8 Weekly, Retrieved 30 sept 2009.

- ^ "Bad Grandpa: The Ballad of Murad the Captain", Jim Billiter. Accessed 9 September 2011

ReferencesEdit

External linksEdit