Code Name 'Angel': Mossad Agent Who Handled Israel's Greatest Spy Speaks Out

What led him to betray his country, how did he make contact with the Israelis, was he a double agent? In an exclusive interview, the man who ran the Egyptian spy Ashraf Marwan tells all

Yossi Melman

On the afternoon of a wintry London day, in December 1970, two tall, thin men entered the lobby of the Royal Lancaster Hotel, next to Hyde Park, separately, one after the other. One was brown-skinned, with dark eyes and thick glasses. The other was fair and blue-eyed. Though they were very excited, they made every effort to behave in a relaxed, natural manner. Sitting in the entrance to the hotel was another man, slightly older than the two, observing the encounter with a skill that was calculated not to betray his own concern and curiosity.

The dark-skinned man was Ashraf Marwan, an Egyptian army officer and businessman, who was then 26 years old. He was to become one of Israel’s most valuable agents. The light-skinned man was Dubi, a Mossad man of 36, whose official title was case officer.

We stood there, the two of us, looking for one another, and then I went up to him and shook his hand,” Dubi says, recollecting their first meeting. “I said to him in Arabic, ‘Let’s sit along the side.’ There was a look of astonishment on his face. I went on talking to him in Arabic. He pulled me into a corner and asked: Where is your Arabic from? But even before I could answer he whispered to me: Don’t talk to me in Arabic. We switched to English.”

After 10 minutes or so of what Dubi calls small talk, the two went up to a room that had been rented the day before by the Mossad station in London, where Dubi was based. Expectations ran high.

“We both went into the room,” Dubi relates. “From his bag he took out documents in Arabic and said to me: I will read to you and you will take notes. He read to me the numbers of all the units in the Egyptian army. Divisions, brigades and battalions. Next to each unit number, he read me the names of the commanders. The commander of this and this division is such and such, and so on. He reads and I write. I was taken aback by the information. It was the dream of every intelligence officer, but I kept a straight face. He read out to me the entire order of battle of the Egyptian army.”

The slightly older man who observed the two, before they went upstairs, was Shmuel Goren, who was 41 at the time. An experienced intelligence officer, Goren commanded the European stations of the Mossad – the Institute for Intelligence and Special Operations, from a base in Brussels. To prepare for the meeting, Goren and the London station had asked the research division of the Israel Defense Forces Intelligence Branch to draw up questions and subjects for the conversation. One issue that particularly interested IDF Military Intelligence was the Egyptian army’s chemical-warfare capabilities

“I asked about the war gases industry and he was surprised by the question – he hadn’t prepared for it,” Dubi says. “He had no answers. I gave him a systematic questionnaire which I had with me, and he promised to reply to it at the next meeting. And in fact, in our next meeting he reported on everything he had collected.”

The first meeting between the two, in London, which lasted about two hours, took place about three months after the death of Egyptian President Gamal Abdel Nasser and the appointment of Anwar Sadat as his successor. Marwan quickly won Sadat’s confidence and for years was his confidant, special adviser and also liaison officer to the Saudi and Libyan intelligence chiefs – with whom he also later conducted private business, mainly involving the sale and purchase of arms. Marwan, Dubi relates, was “like a brother” to Libyan ruler Muammar Gadhafi, “even though he told me a few times that he was majnun [crazy].”

Some time after that initial meeting, the contact between Dubi and Marwan assumed a regular footing. It took place through S., a British Jewish woman, who agreed to allow the phone in her home to be used to convey messages. Marwan would call and leave a bland message containing a code word; that was the signal for her to call Dubi and tell him to come to her apartment, where he waited for the phone to ring again.

Dubi, the Mossad handler, and the gun he was given by Ashraf Marwan.

Dubi, the Mossad handler, and the gun he was given by Ashraf Marwan.

Money, admiration and revenge

Over the years, Mossad and Military Intelligence personnel, journalists and academics have published articles and books and been interviewed in the media about Marwan, the Mossad and the blunders of the Yom Kippur War.

Now, after much mulling, Dubi agreed to speak publicly for the first time, in an exclusive interview to Haaretz, and give his account of his meetings with Marwan and the secret ties he developed with him. For his personal safety, however, Dubi, who will turn 86 this year, does not want his full name to be published. For more than a quarter of a century he was Marwan’s sole handler, holding about 100 meetings with him in hotel rooms and in secured safe houses. The chief venue for their encounters, which added up to many hundreds of hours, was London, but in some cases they met in Rome, Paris and Palma de Mallorca.

Over the years, the two found a common language and came to respect one another, but Dubi never allowed himself to forget that this was not a friendship but a relationship based on vested interests. His mission was to supply information about the intentions and capabilities of Egypt, Israel’s greatest and bitterest enemy, at the time. Marwan, for his part, was driven by a range of motives: a need for money, admiration and respect for the Mossad, personal frustration and a desire for revenge.

The primary motive will probably remain an enigma. On June 27, 2007, Marwan’s body was found lying in the garden of yellow roses below his fifth-floor apartment in London. The London police found it difficult to determine unequivocally whether he committed suicide, fell from his balcony or was pushed by someone who staged the event to make it look like suicide. Former senior personnel of the Mossad and MI have no doubt that the “someone” would have been agents of Egyptian intelligence, who decided to take belated revenge for his betrayal of the homeland. Later, former Mossad chief Zvi Zamir accused Maj. Gen. Eli Zeira, former head of Military Intelligence, of direct responsibility for Marwan’s death, alleging that Zeira had acted tirelessly to get Marwan’s name made public, until that finally happened

It had been Zeira who, as late as the morning of October 6, 1973, predicted a “low probability” of war. In the wake of the war, the special committee of inquiry headed by Supreme Court President Shimon Agranat found Zeira responsible for the intel failure leading up to the war and he was forced to resign. For the past 25 years, Zeira has been attempting to repair his reputation, in part by trying to shift responsibility for the intelligence failure onto the Mossad. To that end, he has been the chief purveyor of the theory that Ashraf Marwan was a double agent. By his logic, if the Mossad and its chief decided to work with a duplicitous player such as Marwan, then they could be blamed for Israel’s failure to anticipate the Arab attack that October day.

‘Chemical’ warning

Dubi’s meetings with Marwan reached their climax some three decades earlier – more precisely, before the Yom Kippur War, which broke out on Saturday, October 6, 1973. Two days beforehand, the phone rang in S.’s apartment: Marwan was on the line from Paris. “Chemicals,” he said to Dubi, who had been awaiting his call: a prearranged code word meaning that war was imminent. Voices of people near Marwan could be heard in the background. “Which chemicals?” Dubi asked quickly. “Many chemicals, a great many,” Marwan replied, to underscore the urgency of the situation.

The code words they had chosen were names of chemical materials. The idea was to give Marwan, who had a degree in chemistry, a cover story and explanation in case a suspicious bystander wanted to know why he was talking about chemical compounds on the phone.

The names of the chemicals bore hidden meanings, referring to sub-questions such as whether war would be launched within one day or two, whether it would begin with an artillery barrage or an aerial attack, and so on. The use of the comprehensive term, “chemicals,” was the most critical of all. Marwan made the call from Paris after returning from a visit to Libya, where he had coordinated between Sadat and Gadhafi in an operation to move every plane belonging to national airline, Egypt Air – wherever it was in the world – to Libya, and to divert the vessels of the Egyptian navy to the safe harbor of Tobruk. Storage of the planes and naval craft, to prevent them from being targeted by Israel, was one of the key preconditions for going to war that Egypt had set itself. Israeli intelligence knew this.

During the October 4 phone call, Marwan said he could not speak for long because there were people around him. He and Dubi agreed to meet the next day in London, with the participation of “the general”: Mossad chief Zamir.

Ashraf Marwan. Illustration.

Ashraf Marwan. Illustration.

Once in London, Marwan met, among others, with the local director of Egypt Air, who confirmed to him that Cairo had ordered the company’s planes to be flown to Libya. The meeting with Dubi and Zamir was scheduled for 9 P.M. , but Marwan was late, as he wanted to get the latest updates via calls to Cairo. He arrived at the safe house, not far from Lord’s, the cricket venue in Northwest London, at 11 P.M. on October 5 (1 A.M. Israel time). Dubi and Zamir were waiting in the apartment, Mossad guards were outside. The meeting went on for three hours.

Dubi drew up a detailed report, based on the minutes he took in the meeting, but he still refuses to make available the transcript (which is deposited in the Mossad archive), and is willing only to reconstruct the spirit of the conversation from memory and paraphrase from it.

Astonishingly, he says, Zamir did not immediately ask about the war, despite Marwan’s warning from the day before and despite the plethora of reports that had been received in the preceding days from additional intelligence sources. Apparently he found it difficult to believe that war was really imminent. Instead, he asked about the triple union of Egypt, Libya and Syria, and then about a plan to blow up an El Al plane at Rome’s Fiumicino Airport that had been concocted not long before by Palestinian terrorists, and which Marwan had helped scuttle. However, the Egyptian agent was impatient. “Let’s talk about the war,” he said to Zamir.

There was a 99 percent probability that war would break out the next day, Marwan said. Zamir asked why on Saturday. “Because that is what was decided,” Marwan replied. “It is a holiday in your country” – a reference to Yom Kippur, the holiest day in the Jewish and Israeli calendar.

Zamir pressed him: How will the war start? Marwan replied that it would be launched simultaneously by Egypt and Syria. Contrary to claims made by various individuals, among them Zeira, over the years, Dubi says that none of the participants in the dramatic meeting in London maintained that the war would erupt at 6 o’clock in the evening. To Zamir’s question of when it would start, Marwan replied: “Sunset.”

The Egyptian agent said that the war had been in the planning for half a year, and that Sadat had decided on the final date on September 25, without telling anyone. According to Marwan, the entire Egyptian army was at the front by that time.

Zamir was not sparing with his questions. One thing Marwan told him was that the Egyptians intended to cross the Suez Canal into Sinai. The Egyptian plan, he said, was to violate the cease-fire reached at the end of the War of Attrition in August 1970 by means of artillery fire and aerial attacks, and then to cross the canal via five or six bridges. The idea in the first stage was to seize territory in Sinai – no more than 10 kilometers deep – and afterward, if the possibility should arise, to advance toward the Mitla and Gidi passes, another 35 kilometers into the peninsula. In the north, the Syrians intended to conquer as much of the Golan Heights as they could.

After Marwan left the meeting, Dubi and Zamir walked to the apartment of the chief of the British station, Rafi Meidan, a few minutes away. On the way, Zamir wondered aloud – perhaps talking to himself, perhaps to Dubi – about what message to send to Israel. He was apprehensive that if he were to announce that war was imminent and then no war broke out, as had happened twice, in May 1972 and sometime between April and June 1973, he would be ridiculed and accused of being a panic-monger. On the other hand, if he were to say that no war was expected and then war should break out, the situation would be very dire.

Upon arriving at Meidan’s apartment, Zamir arrived at a clear decision. In short order he got on the line to the head of his office in Israel, Freddy Eini, and dictated a few sentences to him in prearranged code. War, he told Eini, would erupt (today, Saturday) “at sunset.” From there the message was passed on to Prime Minister Golda Meir.

IDF Chief of Staff David Elazar (right) with Eli Zeira and other top brass during the Yom Kippur War. IDF Archives, Defense Ministry

IDF Chief of Staff David Elazar (right) with Eli Zeira and other top brass during the Yom Kippur War. IDF Archives, Defense Ministry

In retrospect, it turned out that some Israeli leaders, notably Defense Minister Moshe Dayan and several IDF generals, were not attentive to Marwan’s specific words, including his assertions that Egypt’s objections in the war were very limited. Thus, on the war’s third day they panicked and spoke in terms of “the destruction of the Third Temple,” by which they meant the State of Israel itself. According to information published in the 1990s by Israeli historian Avner Cohen, Israel considered deploying its nuclear force, in case the need to use it should arise.

From one ‘Office’ to another

Dubi was born in 1934, in Tel Aviv. His father was a clerk in the Bnei Binyamin Bank, which assisted farmers; his mother, a homemaker. When he was 6, the family moved to Haifa. Until ninth grade he attended the city’s prestigious Reali School, then switched to a vocational school. He entered the IDF in 1952.

“I was thin as a stick and had a heart murmur, so I wasn’t posted to a combat unit but was sent to the air force,” to a support unit. After completing his regular service, he did a course for reserve officers in the Armored Corps and Engineering Corps. He was married in 1958 and the couple’s firstborn, a son, arrived two years later, followed afterward by two more.

By then, Dubi was studying literature and Arabic at the Hebrew University of Jerusalem. “From an early age I was interested in Arabic literature,” he says. “My father encouraged me in that. He spoke Arabic and saw to it that he had good teachers. He loved the language and was meticulous about the accent.” Like his father, Dubi says, he too was strict about speaking Arabic properly, “because to speak Arabic like an Israeli is a joke.”

During his studies he obtained a job in the Prime Minister’s Office: translating letters sent to David Ben-Gurion from Arab citizens. “Some of the letters were illegible, and from them I learned how to decipher manuscripts in Arabic, which helped me afterward when I joined the ‘Office,’” as Mossad employees call their place of work to this day.

The thrust of his employment changed in 1960, when Dubi accepted an offer to join the military administration that then ruled Israel’s Arab population. He served in that capacity for six years, during which he underwent an intelligence course, until his contract – along with the military administration itself – expired. In 1966, he was accepted to the Mossad and assigned to the Tzomet division, which is responsible for recruiting and running agents, then headed by Rehavia Vardi. During the Six-Day War the following year, he operated in the West Bank. (“Our mission was to map the area, and with the aid of acquaintances and conversations with family members in Judea and Samaria, to examine whom it would be possible to recruit [as sources, among Palestinians] in Europe.”) Afterward he did a brief course in intelligence-gathering, but even before that he had met Shimon Gur, who had previously served in IDF intelligence unit 154. In 1968, Gur, the station chief in London, brought in Dubi as a case officer.

The station’s output was meager; high-caliber agents were hard to come by. “Our operation was pretty slipshod,” Dubi recalls. “Little care was taken about security of movement or eavesdropping, and people behaved as though they were in Tel Aviv. I have no doubt that the British listened in on us and learned a lot. I’m certain that nowadays our people do better work and are more cautious.”

Some time later, in 1969 or early 1970, Gur was replaced by Baruch Bardin, and Shmuel Goren took over from Rafi Eitan in Brussels as head of Europe. “Goren was very authoritative and creative, a commander who knew how to make decisions,” Dubi says, “but also tough.”

The turning point in Dubi’s life occurred by chance in December 1970. Goren was touring the Mossad station in Europe and had arrived in London. In the course of a chat, the military attaché, Maj. Gen. Shmuel Eyal, told him that for the past few days he had been getting phone calls at his office in the embassy and at home from someone named Ashraf Marwan, “who’s nagging us and bothering my wife.”

Goren was stunned. “Why didn’t you pass on the conversation to the Mossad, as you should have done?” he asked angrily. Eyal replied, “I don’t know who he is, and I get calls from all kinds of people all the time.”

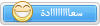

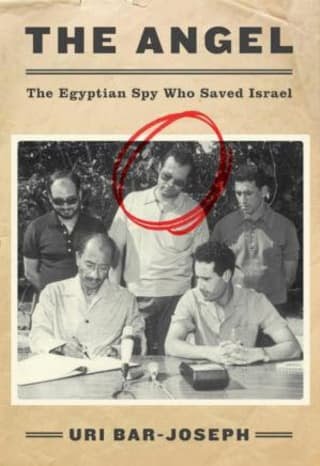

Ashraf Marwan on the cover of Uri Bar-Joseph's book "The Angel: The Egyptian Spy Who Saved Israel." Eyal evron / HarperCollins Publ

Ashraf Marwan on the cover of Uri Bar-Joseph's book "The Angel: The Egyptian Spy Who Saved Israel." Eyal evron / HarperCollins Publ

Goren decided to investigate further. He discovered that Marwan, whose name he knew from the files, had called the attaché’s office several times, as well as his London home, and had left messages that went unanswered. The messages indicated that he would be leaving London the next day. Goren decided to lose no time. He proceeded contrary to operational doctrine, by which an agent must organize every meeting well, examine the background of the person he is meeting, ensure that he is not followed and take other security precautions. “I took a big risk,” Goren told Haaretz recently, “but I didn’t want to miss the opportunity.”

Because the others in the mission were occupied with other tasks, Goren assigned Dubi, who was by now deputy head of mission, to make contact with Marwan. Goren was not entirely pleased with his choice, as Dubi was a young and inexperienced case officer, but in his eyes the mission was “a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity not to be missed.”

Goren and Bardin, the station chief, organized quickly. The phone number Marwan had given them was that of the Egyptian military attaché’s office in London. This was testimony to his brazenness, boldness, self-confidence and, above all, his carelessness – traits that were to characterize him throughout all the years that he worked with Dubi. With the aid of a collaborator with the station, contact was made with Marwan and the meeting at the Royal Lancaster was in 2002arranged.

Nightclubs and gambling

Marwan’s biography could have indicated what then followed. He was born on February 2, 1944, in Cairo. His father had a long military career, achieving the rank of major general (liwwa). He was not part of the Free Officers group that toppled King Farouq in 1952, but the family was close to senior officers who held key posts in the Egyptian government.

Marwan graduated from Kubri al-Quba High School in the science track with high grades, enabling him to put off military service while he pursued undergraduate studies in chemistry. In 1965, he began work as an army officer and chemical engineer in a facility of Egypt’s military industry.

During his studies, Marwan developed a fondness for sports and good times; he played tennis avidly at the prestigious sports club in Cairo’s Heliopolis neighborhood. There, in 1965, in the club, he met Mona, who would become his wife and his ticket to Egypt’s political, military and business establishment.

Three years younger than Marwan, Mona was the younger daughter of Nasser, Egypt’s powerful and charismatic president. A university student at the time, she fell in love with Marwan at first sight. When she told her suspicious father about her feelings, he ordered his bureau chief, Sami Sharaf, to trail the man she loved. Sharaf’s report painted Marwan as an ambitious and frivolous young man who was drawn to a life of glamor, money and good times. Nasser opposed the match, but to no avail: Marwan and Mona were married in July 1966.

Nasser quickly realized that his initial instincts had been right. Everything that had been written about Marwan, and additional information, confirmed Sharaf’s findings. Marwan visited London several times after he was married, carousing in night clubs and casinos. He piled up debts and borrowed money from friends. Nasser did all he could to keep him under surveillance. He even considered forcing his daughter to get a divorce, but to no avail.

Amid all this, the Six-Day War, in June 1967, handed Egypt a shameful defeat and left Nasser humiliated. The Egyptian leader found it difficult to recover from the debacle and died of a heart attack in September 1970. He was just 52. Anwar Sadat was appointed to succeed him.

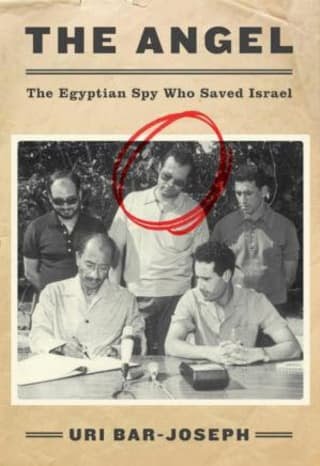

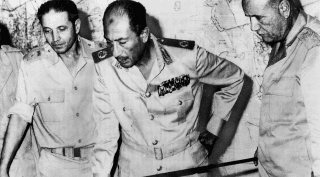

Egypt's Chief-of-Staff Saad el-Shazly (left), President Anwar Sadat (center) and Minister of War Ismail Ali review battlefield developments in 1973. Ann Ronan Picture Library / Photo12 / AFP

Egypt's Chief-of-Staff Saad el-Shazly (left), President Anwar Sadat (center) and Minister of War Ismail Ali review battlefield developments in 1973. Ann Ronan Picture Library / Photo12 / AFP

Caution: Volunteer ahead

That was the lead-up to the meeting in the London hotel. It later turned out that Marwan had tried to make contact with Israel while Nasser was still alive. In the spring of 1970, a few months before his father-in-law’s death, he called Brigadier General Aharon Avnon, the military attaché in Israel’s London embassy, but got no response. Despite his disappointment, he did not let up. Half a year later, he tried his luck again, this time successfully, thanks to Goren’s resourcefulness. Marwan became an Israeli intelligence agent. Dubi related that Marwan had tried making contact through Israel’s military attachés, because the Egyptian thought they were Mossad agents.

What do you think were Marwan’s motives in contacting Israel?

Dubi: “I never asked about his motives. That’s the sort of question a handler doesn’t ask an agent. Naturally, the question of the motives bothered headquarters in Tel Aviv and our people in Brussels very much. They wanted very much to know why he had come to us. Intelligence personnel don’t like volunteers and are wary of them.”

Still, from your long acquaintance with him, what drove him?

“I agree with Goren, who said on several occasions that he wanted money and lots of it. There were other things, too. The Mossad had a very strong image after 1967. He admired the Mossad. In my opinion, Nasser, who had struck fear into Marwan, was very much weakened after the Six-Day War, partly because of his illness. Marwan apparently lost his fear of Nasser and wanted to take revenge on him [for his hostility toward him, for not taking him seriously and for his efforts to break up his marriage]. That’s apparently another reason that he tried to contact us originally, when Nasser was still alive. Nasser disdained him and held him in low esteem.”

Sadat, in contrast, “admired Marwan,” Dubi says. “He promoted him and made him his confidant.” The president’s appreciation of him was bolstered in the winter of 1971 when Sami Sharaf and other leading Nasserists tried to depose Sadat.

“They brought in Marwan, who quickly reported to Sadat about it,” he adds. “Thanks to the information provided by Marwan, Sadat blocked his opponents and made him his trusted special adviser.” Nevertheless, “The fact that Sadat drew him close did not alter Marwan’s contempt for him or the ridicule he heaped on his wife, Jehan, and their children. Marwan told me a few times before the war that Sadat was hesitant and found it hard to make decisions.”

According to Dubi, another reason for Marwan’s anger at Sadat was that at a certain stage, he started to give him tasks such as escorting his wife and daughters on shopping expeditions in Cairo and abroad – something like the family butler.

Hence, his relationship with the Mossad. Naturally, he didn’t provide his valuable information for free, to put it mildly. He said he needed the large sums of money he asked for because he had to look after himself, ensure his safety. “He talked to me about his security,” Dubi recalls, “if he were to be caught and be unable to return to Egypt, or if he came under suspicion. I replied with a question – ‘How much do you think it should be?’ – and his response was: ‘I leave it to you.’”

At first it was decided to pay Marwan only a few thousand dollars each time he provided information, but that riled him. “I’m giving you such good material and this is what you’re giving me? I want 20,000,” Dubi recalls Marwan saying. Goren and other senior Mossad figures vehemently objected: Such a sum was unprecedented; no agent had ever received that much money. In today’s terms, the amount quoted by Marwan would be the equivalent of more than $100,000.

“I recommended acceding to his request, based on the understanding that this would be a long-term relationship and it would be a worthwhile investment that would bear fruit, and we should not bargain with him,” Dubi explains. His recommendation was accepted by Zamir. The payments, which increased over time, were almost always in cash (only once was money deposited in a bank account). Mossad headquarters prepared the banknotes and, like in the movies, placed them in Samsonite suitcases, which were sent to Dubi, who passed them on to Marwan.

“He never counted the money, except for one time,” Dubi adds drily, recalling an amusing incident during one of their meetings. “A suitcase arrived with a relatively large sum, maybe 50,000 in pounds and dollars. Surprisingly, Marwan said to me, ‘Let’s see.’ I opened the suitcase and we saw the money stacked in rows of bundles. Very nice, Marwan said – but then he couldn’t shut the suitcase. I sat on it, and together with him we pushed and pushed until we got it shut.” Goren and Dubi estimate that over the years Marwan was paid close to a million dollars, in today’s terms.

Following the Yom Kippur War, and after he grew wealthy from arms deals he made throughout the Arab world, Marwan announced that there was no longer any need to pay him. “I am thankful for what you did for me, but now I have my own security,” he told Dubi. “I don’t want to be your salaried employee, and from now on I will do it voluntarily, from friendship.”

From that point until he stopped being an agent, Marwan passed on his reports without getting anything in return. “From the mid-1970s he was a rich man,” Dubi notes. “He exploited positions in the government and connections in order to get rich.”

Ashraf Marwan, in the '90s. AFP

Personal pistol

The interview with Dubi was conducted in a Tel Aviv café over the course of several days. One of the issues that came up was the fact that Marwan was in contact not only with the Mossad but also with other intelligence services, among them those of the United Kingdom and Italy. “True,” Dubi says. “He had connections with many people, including Western services. That was his assignment, while serving as Sadat’s special adviser. But the Mossad was the only one he got money from, and he can be termed a paid agent.”

Over the years Dubi and his managers, as is customary in the world of espionage, gave Marwan a number of code names, among them “Atmos,” “Pacety,” “The Angel,” “Hutel” and “Rashash.” Dubi always introduced himself as ‘Alex.” “One day, he asked me: ‘Is your name really Alex?’ No, I told him, that’s my cover name. He thanked me for my honesty.”

I asked Dubi if he could remember another interesting anecdote from his meetings with Marwan. “Yes,” he replied with a smile and, with the agility of an experienced gunman, pulled a small pistol out of his coat pocket and placed it on the table.

In one of their meetings, Marwan opened his suit jacket and Dubi saw a gun sticking out of his pocket. “What’s that gun? Do you want to shoot me?” Dubi asked with a smile that masked concern and apprehension. Marwan took out a small, loaded Smith & Wesson revolver from his pocket. Dubi tried to persuade him that it was dangerous to walk around London with a firearm and also against the law. Marwan was not convinced. “This revolver is always with me. Don’t worry. I’m careful,” Marwan said reassuringly, and besides that, he added, “Ana ma bathfatas” – “I don’t get searched.”

At their next meeting, Marwan took out a box. “I opened it and saw a Smith & Wesson. ‘It’s for you,’ he told me. I objected, but he refused to take it back. In order not argue with him or offend him, I agreed to take it. I sent the pistol to the Office, and Shmulik [Goren] allowed me to keep it.”

Dubi didn’t miss a single meeting with Marwan in the 28 years in which he was his handler, even after his retirement. At some of the meetings he was joined by Y., a radio technician and an experienced hand with technology. His job was to instruct Marwan in the operation of a wireless radio and other means of communication. The Mossad arranged for Marwan to receive a device in Cairo, but he never used it. Long afterward, when asked what had happened to the device, he replied: I threw it into the Nile. I thought it was too dangerous for me to have it in my possession or to use it.

Aside from Dubi, the person from the agency who spent the most time with Marwan was Zamir, who met with him six or seven times. Zamir explained that he asked to participate in meetings in order to get to know his ace agent better, even though he admitted that it was quite rare for a Mossad chief to come to meetings with his agents. “On the other hand,” Dubi emphasized, “the fact that the Mossad chief in person took the trouble to meet with him flattered Marwan and strengthened the ties with him.”

Zamir went so far as to say that he considered himself “Marwan’s friend.” Goren thinks otherwise – that Zamir wasn’t serious and also that it was in any case wrong for him to feel that way. “Agents, even the most important of them, are not friends and should not be friends of the Mossad head.”

Zamir retired from the Mossad in 1974. His successor, Yitzhak Hofi, also decided to meet with Marwan – once, in Dubi’s presence. Over the years, no few people in the Mossad coveted Dubi’s assignment and wanted to replace him. “Case officers envied me,” he says.

On three occasions Goren, Zamir, Hofi and Danny Yatom (the Mossad chief during the second half of the 1990s) tried to appoint a new handler for Marwan. And each time they failed. In one case, Marwan didn’t like the Iraqi origins of the intended agency replacement. In another case, a Mossad operative of Anglo-Saxon descent was sent to him, but he too was unable to win over the Egyptian agent.

The third attempt came in 1997, about a decade after Dubi had become a handler in retirement. It was the period of the Yehuda Gil episode – the Mossad case officer who for 20 years fabricated intelligence reports while claiming that his agent, a Syrian general, was willing to meet only with him. In Gil’s trial, on charges of espionage and fraud, in which he was convicted and sentenced to a five-year prison term, it turned out that he had in fact met with the Syrian, but had never succeeded in recruiting him and running him as an agent. The general viewed him as a friend and no more. Gil, who was ashamed to admit his failure, invented reports in which he set forth in great detail his conversations with the general. Senior figures in the Mossad and Military Intelligence bought the story and did not suspect Gil.

Against the background of that case, Mossad chief Yatom decided that case officers would not run agents for more than a few years. “We decided to change the method,” he explained. Accordingly, Dubi was instructed to meet with Marwan in a hotel in Palma de Mallorca. He was told that as soon as he entered the lobby he should ask Marwan to meet him for breakfast and not in his room, as usual. Marwan made a face but agreed. But while they were conversing, Marwan noticed a couple, a man and a woman, who were observing them with suspicious gazes. “They are listening to us,” Marwan said to Dubi, and the two went up to the room.

In the wake of this, because Marwan did not want to work with anyone else, Dubi informed him that their relationship had come to an end. “We embraced and parted as friends,” Dubi recalls. Nevertheless, he acceded to the Mossad’s request to maintain contact with Marwan for a certain period.

Still, in those years there was no longer an intense connection between Marwan and the Mossad. It had grown more lax already by the late 1970s. Marwan’s great importance lay in that decade, not only with the Yom Kippur War, but also after it, during the separation of forces agreements in Sinai and until the Israeli-Egyptian peace treaty in 1979. Afterward, his standing with Sadat declined and Marwan himself devoted increasing time to his own businesses – so his contribution diminished as well. The information he continued to provide about Egypt in an era of peace and ties in the Arab world was indeed important, but it was obvious to all concerned that it did not match the level and quality of the war era. Dubi, too, became involved in other matters over the years, between the meetings with Marwan, and even more so after the latter’s importance declined. During the period of the first Lebanon war, for example, he was sent as a case officer to reinforce Mossad’s operation in that neighboring country.

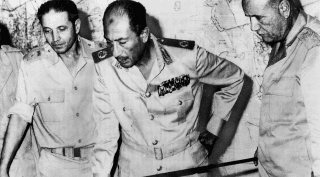

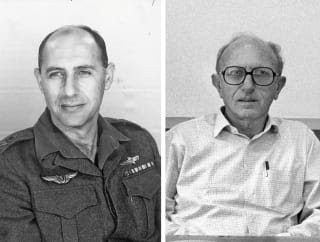

Former Mossad chief Zvi Zamir (right) alleged that Maj. Gen. Eli Zeira, former head of Military Intelligence (left), acted tirelessly to get Marwan’s name made public. Zvika Israeli, GPO / IDF Spokesperson's Unit

Former Mossad chief Zvi Zamir (right) alleged that Maj. Gen. Eli Zeira, former head of Military Intelligence (left), acted tirelessly to get Marwan’s name made public. Zvika Israeli, GPO / IDF Spokesperson's Unit

Battle for his good name

After the relations between Dubi and Marwan were mutually terminated, Dubi became angry. Not because he was longer meeting with the Egyptian, but out of concern for his safety.

The main reason for this, Dubi says, lay in the trickles and leaks from former Military Intelligence director Eli Zeira and his handful of followers, which led to Marwan’s name finally being made public. That happened in December 2002, when Marwan was first identified by name as an Israeli agent, in the Egyptian newspaper Al Ahram. The paper, it turns out, had approached Ahron Bregman, a political scientist of Israeli origin at King’s College, London, to confirm that the Egyptian who had spied for Israel, whom Bregman claimed was a double agent, was Marwan. The name was subsequently picked up by the international media and eventually, in the Israeli press.

Up until Marwan’s tragic death, in 2007, Dubi tried a number of times, in conversations with Zamir and other senior Mossad figures, to warn against Zeira’s actions. “Twice I wrote to the directorate that there was going to be a disaster. The first time they didn’t answer, and the second time a meeting was held in Tzomet in the presence of the Mossad chief, Meir Dagan. I was not at that meeting, but I saw its summation, in which it was decided to do nothing.”

Decades went by following the events of those days, and Dubi kept silent. Underlying his decision to be interviewed now are not only the 50 years that passed and the fact that “many Mossad people give interviews all the time.” The additional, main, reason is his desire to refute a thesis that has taken wing, according to which Marwan was a “double agent.” Even though the majority of the experts in Israel have confirmed time and again that this is an unfounded, baseless accusation for which no evidence exists, in recent years it has gained support, full or partial, from several journalists and a handful of intelligence officers. Here, too, the central figure is Zeira, who was dismissed from his post because of his blunders in the Yom Kippur War.

In 2007, the issue came up for judicial evaluation. Former Supreme Court Justice Theodor Or was the lone arbitrator in mutual libel cases submitted by Zamir and Zeira. Or ruled explicitly that Marwan was not a double agent and that Zeira had leaked the source’s name to journalists and writers. These leaks, or Zeira’s systematic efforts to reveal Marwan’s identity, as Dubi and Zamir term them, led to his death, they say. “We [Israel] murdered him,” Zamir told me at the time, acknowledging that he was really referring to Zeira.

Subsequently, the state prosecution weighed launch criminal proceedings against Zeira, on grounds of violating state security and revealing state secrets. In 2012, however, the attorney general, Yehuda Weinstein, announced that he had decided not to charge Zeira. He wrote that even though the “gravity of the deeds” alleged against Zeira could not be denied, he had decided to take into consideration his age (84) and the fact that he had “done much in the struggle to establish the state and to preserve its security.”

Dubi hopes that the present interview will refute once and for all “Zeira’s lies,” as he puts it. “He was the most important spy we had, and the information he provided was intended to contribute to Israel’s security,” Dubi says. “Unfortunately, at the most important moment, in the Yom Kippur War, Israel failed because it did not heed the warnings he provided.”

A cornerstone of the double-agent theory has to do with Marwan’s modes of moving around. In all his many trips abroad, on business, for diplomatic meetings and for meetings with Mossad personnel, the agent carried an Egyptian diplomatic passport. In one case, he was driven to a meeting by a driver from the Egyptian embassy in London, in a car that bore diplomatic license plates. Marwan got off a few streets from the venue and the driver went on his way. Afterward, Zvi Malhin, who founded the Mossad’s Keshet division, which is in charge of surveillance, and as such was also responsible for securing one of the meetings with Marwan, claimed that this attested to his being a double agent. Dubi, Zamir, Goren and others see Marwan’s behavior as proving precisely that he was not a double agent. “If he had been a double agent whose loyalty was to Egypt, he would have been cautious about every indication, such as an embassy driver, that could make Israel suspicious of him.”

Another instance that underlay this thesis was Marwan’s death, and more precisely the magnificent funeral held for him, with the participation of President Hosni Mubarak and the Egyptian ruling hierarchy. “It was like a scene from the movies,” Dubi says. “The head of the mafia liquidates his deputy, goes to the funeral and tells the widow and the deceased’s friends what a wonderful and important person he was, who made a contribution to society. Marwan was flesh of the flesh of the top ranks of the Egyptian establishment. In the eyes of the Egyptians the Yom Kippur War was a glorious victory. So why stain the event with a story about a spy and a traitor?”

When all is said and done, Dubi adds, he has in his possession – “and there is also in the possession of others who were involved in the matter” – what he says is “more than enough evidence to prove that Marwan was a genuine, high-quality agent who helped Israel.” What proof does he have? It is diverse. For one, he notes the fact that Marwan tried to make contact with Israel as early as the period when Nasser was still president. Because Nasser’s dislike of his son-in-law was so powerful, he tried to distance him from the centers of government, “and therefore it is hard to imagine that Nasser would have suggested that he spy for Egypt.”

But more important, he insists, “The reports supplied by Marwan need to be judged for their quality and for their contribution to Israeli intelligence, and there is no denying that. He supplied information about the Egyptian order of battle and about the war plans, including the smuggling of the planes and ships to Libya before the war. Twice he provided reports about plans of terrorist organizations and Libya to bring down El Al planes with shoulder-fired missiles. All his information proved to be correct and precise.”

With regard to Egypt, too, he relates, even before the Yom Kippur War, Marwan “provided a number of warnings and information that proved to be correct.” Among other information, he reported, weeks before the war, that on October 24, 1972, a year earlier, Sadat decided to step up the preparations for war and to that end dismissed Defense Minister Sadek; in April 1973, he provided information that Syrian President Hafez Assad had met in Cairo with Sadat and the two had coordinated their moves in the war – in their meeting they decided to postpone the date, from April to June, in order to allow for acquisition of more weapons; afterward he reported that the June date had been postponed, so that Egypt could integrate more antiaircraft batteries and Scud missiles purchased from the Soviets; and in July he reported that Sadat had suggested to Assad yet another date for the war, at the end of September or early October.

And then came the war. “Marwan reported on the night between Friday and Saturday that the war would erupt at sunset,” Dubi recalls. “He didn’t know that Sadat had moved up the opening hour to 2 P.M., as Assad had requested of him a few days earlier. And in any case, would those four hours have changed anything? Would Sadat have risked his strategic plan to go to war, which he had been working on for several years, and conveyed through Marwan a warning about the exact day on which the war would break out? Did Sadat know that the government of Israel would decide not to launch a preemptive strike on Saturday morning after the definitive information arrived via me and Zamir from Marwan?”

However, according to Dubi, the overwhelming proof of Marwan’s reliability lies precisely in Zeira’s central argument for his being a supposed double agent. In August 1973, Sadat and Saudi King Feisal met in Riyadh; Marwan was present at the meeting. Sadat’s aim was to request additional financial aid from Feisal to purchase weapons and to prepare Saudi Arabia to impose an oil embargo upon the start of the war. Zeira maintains consistently that Marwan did not report to the Mossad about that meeting. “That is a lie. Zeira is lying – and how – only to absolve himself of the responsibility and impose it on the Mossad,” Dubi emphasizes. “I met Marwan after the Riyadh meeting, and with my own eyes I saw the material he conveyed to us about that meeting.”

Haaretz asked Zeira about this, but he declined to comment.

What led him to betray his country, how did he make contact with the Israelis, was he a double agent? In an exclusive interview, the man who ran the Egyptian spy Ashraf Marwan tells all

Yossi Melman

On the afternoon of a wintry London day, in December 1970, two tall, thin men entered the lobby of the Royal Lancaster Hotel, next to Hyde Park, separately, one after the other. One was brown-skinned, with dark eyes and thick glasses. The other was fair and blue-eyed. Though they were very excited, they made every effort to behave in a relaxed, natural manner. Sitting in the entrance to the hotel was another man, slightly older than the two, observing the encounter with a skill that was calculated not to betray his own concern and curiosity.

The dark-skinned man was Ashraf Marwan, an Egyptian army officer and businessman, who was then 26 years old. He was to become one of Israel’s most valuable agents. The light-skinned man was Dubi, a Mossad man of 36, whose official title was case officer.

We stood there, the two of us, looking for one another, and then I went up to him and shook his hand,” Dubi says, recollecting their first meeting. “I said to him in Arabic, ‘Let’s sit along the side.’ There was a look of astonishment on his face. I went on talking to him in Arabic. He pulled me into a corner and asked: Where is your Arabic from? But even before I could answer he whispered to me: Don’t talk to me in Arabic. We switched to English.”

After 10 minutes or so of what Dubi calls small talk, the two went up to a room that had been rented the day before by the Mossad station in London, where Dubi was based. Expectations ran high.

“We both went into the room,” Dubi relates. “From his bag he took out documents in Arabic and said to me: I will read to you and you will take notes. He read to me the numbers of all the units in the Egyptian army. Divisions, brigades and battalions. Next to each unit number, he read me the names of the commanders. The commander of this and this division is such and such, and so on. He reads and I write. I was taken aback by the information. It was the dream of every intelligence officer, but I kept a straight face. He read out to me the entire order of battle of the Egyptian army.”

The slightly older man who observed the two, before they went upstairs, was Shmuel Goren, who was 41 at the time. An experienced intelligence officer, Goren commanded the European stations of the Mossad – the Institute for Intelligence and Special Operations, from a base in Brussels. To prepare for the meeting, Goren and the London station had asked the research division of the Israel Defense Forces Intelligence Branch to draw up questions and subjects for the conversation. One issue that particularly interested IDF Military Intelligence was the Egyptian army’s chemical-warfare capabilities

“I asked about the war gases industry and he was surprised by the question – he hadn’t prepared for it,” Dubi says. “He had no answers. I gave him a systematic questionnaire which I had with me, and he promised to reply to it at the next meeting. And in fact, in our next meeting he reported on everything he had collected.”

The first meeting between the two, in London, which lasted about two hours, took place about three months after the death of Egyptian President Gamal Abdel Nasser and the appointment of Anwar Sadat as his successor. Marwan quickly won Sadat’s confidence and for years was his confidant, special adviser and also liaison officer to the Saudi and Libyan intelligence chiefs – with whom he also later conducted private business, mainly involving the sale and purchase of arms. Marwan, Dubi relates, was “like a brother” to Libyan ruler Muammar Gadhafi, “even though he told me a few times that he was majnun [crazy].”

Some time after that initial meeting, the contact between Dubi and Marwan assumed a regular footing. It took place through S., a British Jewish woman, who agreed to allow the phone in her home to be used to convey messages. Marwan would call and leave a bland message containing a code word; that was the signal for her to call Dubi and tell him to come to her apartment, where he waited for the phone to ring again.

Money, admiration and revenge

Over the years, Mossad and Military Intelligence personnel, journalists and academics have published articles and books and been interviewed in the media about Marwan, the Mossad and the blunders of the Yom Kippur War.

Now, after much mulling, Dubi agreed to speak publicly for the first time, in an exclusive interview to Haaretz, and give his account of his meetings with Marwan and the secret ties he developed with him. For his personal safety, however, Dubi, who will turn 86 this year, does not want his full name to be published. For more than a quarter of a century he was Marwan’s sole handler, holding about 100 meetings with him in hotel rooms and in secured safe houses. The chief venue for their encounters, which added up to many hundreds of hours, was London, but in some cases they met in Rome, Paris and Palma de Mallorca.

Over the years, the two found a common language and came to respect one another, but Dubi never allowed himself to forget that this was not a friendship but a relationship based on vested interests. His mission was to supply information about the intentions and capabilities of Egypt, Israel’s greatest and bitterest enemy, at the time. Marwan, for his part, was driven by a range of motives: a need for money, admiration and respect for the Mossad, personal frustration and a desire for revenge.

The primary motive will probably remain an enigma. On June 27, 2007, Marwan’s body was found lying in the garden of yellow roses below his fifth-floor apartment in London. The London police found it difficult to determine unequivocally whether he committed suicide, fell from his balcony or was pushed by someone who staged the event to make it look like suicide. Former senior personnel of the Mossad and MI have no doubt that the “someone” would have been agents of Egyptian intelligence, who decided to take belated revenge for his betrayal of the homeland. Later, former Mossad chief Zvi Zamir accused Maj. Gen. Eli Zeira, former head of Military Intelligence, of direct responsibility for Marwan’s death, alleging that Zeira had acted tirelessly to get Marwan’s name made public, until that finally happened

It had been Zeira who, as late as the morning of October 6, 1973, predicted a “low probability” of war. In the wake of the war, the special committee of inquiry headed by Supreme Court President Shimon Agranat found Zeira responsible for the intel failure leading up to the war and he was forced to resign. For the past 25 years, Zeira has been attempting to repair his reputation, in part by trying to shift responsibility for the intelligence failure onto the Mossad. To that end, he has been the chief purveyor of the theory that Ashraf Marwan was a double agent. By his logic, if the Mossad and its chief decided to work with a duplicitous player such as Marwan, then they could be blamed for Israel’s failure to anticipate the Arab attack that October day.

‘Chemical’ warning

Dubi’s meetings with Marwan reached their climax some three decades earlier – more precisely, before the Yom Kippur War, which broke out on Saturday, October 6, 1973. Two days beforehand, the phone rang in S.’s apartment: Marwan was on the line from Paris. “Chemicals,” he said to Dubi, who had been awaiting his call: a prearranged code word meaning that war was imminent. Voices of people near Marwan could be heard in the background. “Which chemicals?” Dubi asked quickly. “Many chemicals, a great many,” Marwan replied, to underscore the urgency of the situation.

The code words they had chosen were names of chemical materials. The idea was to give Marwan, who had a degree in chemistry, a cover story and explanation in case a suspicious bystander wanted to know why he was talking about chemical compounds on the phone.

The names of the chemicals bore hidden meanings, referring to sub-questions such as whether war would be launched within one day or two, whether it would begin with an artillery barrage or an aerial attack, and so on. The use of the comprehensive term, “chemicals,” was the most critical of all. Marwan made the call from Paris after returning from a visit to Libya, where he had coordinated between Sadat and Gadhafi in an operation to move every plane belonging to national airline, Egypt Air – wherever it was in the world – to Libya, and to divert the vessels of the Egyptian navy to the safe harbor of Tobruk. Storage of the planes and naval craft, to prevent them from being targeted by Israel, was one of the key preconditions for going to war that Egypt had set itself. Israeli intelligence knew this.

During the October 4 phone call, Marwan said he could not speak for long because there were people around him. He and Dubi agreed to meet the next day in London, with the participation of “the general”: Mossad chief Zamir.

Once in London, Marwan met, among others, with the local director of Egypt Air, who confirmed to him that Cairo had ordered the company’s planes to be flown to Libya. The meeting with Dubi and Zamir was scheduled for 9 P.M. , but Marwan was late, as he wanted to get the latest updates via calls to Cairo. He arrived at the safe house, not far from Lord’s, the cricket venue in Northwest London, at 11 P.M. on October 5 (1 A.M. Israel time). Dubi and Zamir were waiting in the apartment, Mossad guards were outside. The meeting went on for three hours.

Dubi drew up a detailed report, based on the minutes he took in the meeting, but he still refuses to make available the transcript (which is deposited in the Mossad archive), and is willing only to reconstruct the spirit of the conversation from memory and paraphrase from it.

Astonishingly, he says, Zamir did not immediately ask about the war, despite Marwan’s warning from the day before and despite the plethora of reports that had been received in the preceding days from additional intelligence sources. Apparently he found it difficult to believe that war was really imminent. Instead, he asked about the triple union of Egypt, Libya and Syria, and then about a plan to blow up an El Al plane at Rome’s Fiumicino Airport that had been concocted not long before by Palestinian terrorists, and which Marwan had helped scuttle. However, the Egyptian agent was impatient. “Let’s talk about the war,” he said to Zamir.

There was a 99 percent probability that war would break out the next day, Marwan said. Zamir asked why on Saturday. “Because that is what was decided,” Marwan replied. “It is a holiday in your country” – a reference to Yom Kippur, the holiest day in the Jewish and Israeli calendar.

Zamir pressed him: How will the war start? Marwan replied that it would be launched simultaneously by Egypt and Syria. Contrary to claims made by various individuals, among them Zeira, over the years, Dubi says that none of the participants in the dramatic meeting in London maintained that the war would erupt at 6 o’clock in the evening. To Zamir’s question of when it would start, Marwan replied: “Sunset.”

The Egyptian agent said that the war had been in the planning for half a year, and that Sadat had decided on the final date on September 25, without telling anyone. According to Marwan, the entire Egyptian army was at the front by that time.

Zamir was not sparing with his questions. One thing Marwan told him was that the Egyptians intended to cross the Suez Canal into Sinai. The Egyptian plan, he said, was to violate the cease-fire reached at the end of the War of Attrition in August 1970 by means of artillery fire and aerial attacks, and then to cross the canal via five or six bridges. The idea in the first stage was to seize territory in Sinai – no more than 10 kilometers deep – and afterward, if the possibility should arise, to advance toward the Mitla and Gidi passes, another 35 kilometers into the peninsula. In the north, the Syrians intended to conquer as much of the Golan Heights as they could.

After Marwan left the meeting, Dubi and Zamir walked to the apartment of the chief of the British station, Rafi Meidan, a few minutes away. On the way, Zamir wondered aloud – perhaps talking to himself, perhaps to Dubi – about what message to send to Israel. He was apprehensive that if he were to announce that war was imminent and then no war broke out, as had happened twice, in May 1972 and sometime between April and June 1973, he would be ridiculed and accused of being a panic-monger. On the other hand, if he were to say that no war was expected and then war should break out, the situation would be very dire.

Upon arriving at Meidan’s apartment, Zamir arrived at a clear decision. In short order he got on the line to the head of his office in Israel, Freddy Eini, and dictated a few sentences to him in prearranged code. War, he told Eini, would erupt (today, Saturday) “at sunset.” From there the message was passed on to Prime Minister Golda Meir.

In retrospect, it turned out that some Israeli leaders, notably Defense Minister Moshe Dayan and several IDF generals, were not attentive to Marwan’s specific words, including his assertions that Egypt’s objections in the war were very limited. Thus, on the war’s third day they panicked and spoke in terms of “the destruction of the Third Temple,” by which they meant the State of Israel itself. According to information published in the 1990s by Israeli historian Avner Cohen, Israel considered deploying its nuclear force, in case the need to use it should arise.

From one ‘Office’ to another

Dubi was born in 1934, in Tel Aviv. His father was a clerk in the Bnei Binyamin Bank, which assisted farmers; his mother, a homemaker. When he was 6, the family moved to Haifa. Until ninth grade he attended the city’s prestigious Reali School, then switched to a vocational school. He entered the IDF in 1952.

“I was thin as a stick and had a heart murmur, so I wasn’t posted to a combat unit but was sent to the air force,” to a support unit. After completing his regular service, he did a course for reserve officers in the Armored Corps and Engineering Corps. He was married in 1958 and the couple’s firstborn, a son, arrived two years later, followed afterward by two more.

By then, Dubi was studying literature and Arabic at the Hebrew University of Jerusalem. “From an early age I was interested in Arabic literature,” he says. “My father encouraged me in that. He spoke Arabic and saw to it that he had good teachers. He loved the language and was meticulous about the accent.” Like his father, Dubi says, he too was strict about speaking Arabic properly, “because to speak Arabic like an Israeli is a joke.”

During his studies he obtained a job in the Prime Minister’s Office: translating letters sent to David Ben-Gurion from Arab citizens. “Some of the letters were illegible, and from them I learned how to decipher manuscripts in Arabic, which helped me afterward when I joined the ‘Office,’” as Mossad employees call their place of work to this day.

The thrust of his employment changed in 1960, when Dubi accepted an offer to join the military administration that then ruled Israel’s Arab population. He served in that capacity for six years, during which he underwent an intelligence course, until his contract – along with the military administration itself – expired. In 1966, he was accepted to the Mossad and assigned to the Tzomet division, which is responsible for recruiting and running agents, then headed by Rehavia Vardi. During the Six-Day War the following year, he operated in the West Bank. (“Our mission was to map the area, and with the aid of acquaintances and conversations with family members in Judea and Samaria, to examine whom it would be possible to recruit [as sources, among Palestinians] in Europe.”) Afterward he did a brief course in intelligence-gathering, but even before that he had met Shimon Gur, who had previously served in IDF intelligence unit 154. In 1968, Gur, the station chief in London, brought in Dubi as a case officer.

The station’s output was meager; high-caliber agents were hard to come by. “Our operation was pretty slipshod,” Dubi recalls. “Little care was taken about security of movement or eavesdropping, and people behaved as though they were in Tel Aviv. I have no doubt that the British listened in on us and learned a lot. I’m certain that nowadays our people do better work and are more cautious.”

Some time later, in 1969 or early 1970, Gur was replaced by Baruch Bardin, and Shmuel Goren took over from Rafi Eitan in Brussels as head of Europe. “Goren was very authoritative and creative, a commander who knew how to make decisions,” Dubi says, “but also tough.”

The turning point in Dubi’s life occurred by chance in December 1970. Goren was touring the Mossad station in Europe and had arrived in London. In the course of a chat, the military attaché, Maj. Gen. Shmuel Eyal, told him that for the past few days he had been getting phone calls at his office in the embassy and at home from someone named Ashraf Marwan, “who’s nagging us and bothering my wife.”

Goren was stunned. “Why didn’t you pass on the conversation to the Mossad, as you should have done?” he asked angrily. Eyal replied, “I don’t know who he is, and I get calls from all kinds of people all the time.”

Goren decided to investigate further. He discovered that Marwan, whose name he knew from the files, had called the attaché’s office several times, as well as his London home, and had left messages that went unanswered. The messages indicated that he would be leaving London the next day. Goren decided to lose no time. He proceeded contrary to operational doctrine, by which an agent must organize every meeting well, examine the background of the person he is meeting, ensure that he is not followed and take other security precautions. “I took a big risk,” Goren told Haaretz recently, “but I didn’t want to miss the opportunity.”

Because the others in the mission were occupied with other tasks, Goren assigned Dubi, who was by now deputy head of mission, to make contact with Marwan. Goren was not entirely pleased with his choice, as Dubi was a young and inexperienced case officer, but in his eyes the mission was “a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity not to be missed.”

Goren and Bardin, the station chief, organized quickly. The phone number Marwan had given them was that of the Egyptian military attaché’s office in London. This was testimony to his brazenness, boldness, self-confidence and, above all, his carelessness – traits that were to characterize him throughout all the years that he worked with Dubi. With the aid of a collaborator with the station, contact was made with Marwan and the meeting at the Royal Lancaster was in 2002arranged.

Nightclubs and gambling

Marwan’s biography could have indicated what then followed. He was born on February 2, 1944, in Cairo. His father had a long military career, achieving the rank of major general (liwwa). He was not part of the Free Officers group that toppled King Farouq in 1952, but the family was close to senior officers who held key posts in the Egyptian government.

Marwan graduated from Kubri al-Quba High School in the science track with high grades, enabling him to put off military service while he pursued undergraduate studies in chemistry. In 1965, he began work as an army officer and chemical engineer in a facility of Egypt’s military industry.

During his studies, Marwan developed a fondness for sports and good times; he played tennis avidly at the prestigious sports club in Cairo’s Heliopolis neighborhood. There, in 1965, in the club, he met Mona, who would become his wife and his ticket to Egypt’s political, military and business establishment.

Three years younger than Marwan, Mona was the younger daughter of Nasser, Egypt’s powerful and charismatic president. A university student at the time, she fell in love with Marwan at first sight. When she told her suspicious father about her feelings, he ordered his bureau chief, Sami Sharaf, to trail the man she loved. Sharaf’s report painted Marwan as an ambitious and frivolous young man who was drawn to a life of glamor, money and good times. Nasser opposed the match, but to no avail: Marwan and Mona were married in July 1966.

Nasser quickly realized that his initial instincts had been right. Everything that had been written about Marwan, and additional information, confirmed Sharaf’s findings. Marwan visited London several times after he was married, carousing in night clubs and casinos. He piled up debts and borrowed money from friends. Nasser did all he could to keep him under surveillance. He even considered forcing his daughter to get a divorce, but to no avail.

Amid all this, the Six-Day War, in June 1967, handed Egypt a shameful defeat and left Nasser humiliated. The Egyptian leader found it difficult to recover from the debacle and died of a heart attack in September 1970. He was just 52. Anwar Sadat was appointed to succeed him.

Caution: Volunteer ahead

That was the lead-up to the meeting in the London hotel. It later turned out that Marwan had tried to make contact with Israel while Nasser was still alive. In the spring of 1970, a few months before his father-in-law’s death, he called Brigadier General Aharon Avnon, the military attaché in Israel’s London embassy, but got no response. Despite his disappointment, he did not let up. Half a year later, he tried his luck again, this time successfully, thanks to Goren’s resourcefulness. Marwan became an Israeli intelligence agent. Dubi related that Marwan had tried making contact through Israel’s military attachés, because the Egyptian thought they were Mossad agents.

What do you think were Marwan’s motives in contacting Israel?

Dubi: “I never asked about his motives. That’s the sort of question a handler doesn’t ask an agent. Naturally, the question of the motives bothered headquarters in Tel Aviv and our people in Brussels very much. They wanted very much to know why he had come to us. Intelligence personnel don’t like volunteers and are wary of them.”

Still, from your long acquaintance with him, what drove him?

“I agree with Goren, who said on several occasions that he wanted money and lots of it. There were other things, too. The Mossad had a very strong image after 1967. He admired the Mossad. In my opinion, Nasser, who had struck fear into Marwan, was very much weakened after the Six-Day War, partly because of his illness. Marwan apparently lost his fear of Nasser and wanted to take revenge on him [for his hostility toward him, for not taking him seriously and for his efforts to break up his marriage]. That’s apparently another reason that he tried to contact us originally, when Nasser was still alive. Nasser disdained him and held him in low esteem.”

Sadat, in contrast, “admired Marwan,” Dubi says. “He promoted him and made him his confidant.” The president’s appreciation of him was bolstered in the winter of 1971 when Sami Sharaf and other leading Nasserists tried to depose Sadat.

“They brought in Marwan, who quickly reported to Sadat about it,” he adds. “Thanks to the information provided by Marwan, Sadat blocked his opponents and made him his trusted special adviser.” Nevertheless, “The fact that Sadat drew him close did not alter Marwan’s contempt for him or the ridicule he heaped on his wife, Jehan, and their children. Marwan told me a few times before the war that Sadat was hesitant and found it hard to make decisions.”

According to Dubi, another reason for Marwan’s anger at Sadat was that at a certain stage, he started to give him tasks such as escorting his wife and daughters on shopping expeditions in Cairo and abroad – something like the family butler.

Hence, his relationship with the Mossad. Naturally, he didn’t provide his valuable information for free, to put it mildly. He said he needed the large sums of money he asked for because he had to look after himself, ensure his safety. “He talked to me about his security,” Dubi recalls, “if he were to be caught and be unable to return to Egypt, or if he came under suspicion. I replied with a question – ‘How much do you think it should be?’ – and his response was: ‘I leave it to you.’”

At first it was decided to pay Marwan only a few thousand dollars each time he provided information, but that riled him. “I’m giving you such good material and this is what you’re giving me? I want 20,000,” Dubi recalls Marwan saying. Goren and other senior Mossad figures vehemently objected: Such a sum was unprecedented; no agent had ever received that much money. In today’s terms, the amount quoted by Marwan would be the equivalent of more than $100,000.

“I recommended acceding to his request, based on the understanding that this would be a long-term relationship and it would be a worthwhile investment that would bear fruit, and we should not bargain with him,” Dubi explains. His recommendation was accepted by Zamir. The payments, which increased over time, were almost always in cash (only once was money deposited in a bank account). Mossad headquarters prepared the banknotes and, like in the movies, placed them in Samsonite suitcases, which were sent to Dubi, who passed them on to Marwan.

“He never counted the money, except for one time,” Dubi adds drily, recalling an amusing incident during one of their meetings. “A suitcase arrived with a relatively large sum, maybe 50,000 in pounds and dollars. Surprisingly, Marwan said to me, ‘Let’s see.’ I opened the suitcase and we saw the money stacked in rows of bundles. Very nice, Marwan said – but then he couldn’t shut the suitcase. I sat on it, and together with him we pushed and pushed until we got it shut.” Goren and Dubi estimate that over the years Marwan was paid close to a million dollars, in today’s terms.

Following the Yom Kippur War, and after he grew wealthy from arms deals he made throughout the Arab world, Marwan announced that there was no longer any need to pay him. “I am thankful for what you did for me, but now I have my own security,” he told Dubi. “I don’t want to be your salaried employee, and from now on I will do it voluntarily, from friendship.”

From that point until he stopped being an agent, Marwan passed on his reports without getting anything in return. “From the mid-1970s he was a rich man,” Dubi notes. “He exploited positions in the government and connections in order to get rich.”

Ashraf Marwan, in the '90s. AFP

Personal pistol

The interview with Dubi was conducted in a Tel Aviv café over the course of several days. One of the issues that came up was the fact that Marwan was in contact not only with the Mossad but also with other intelligence services, among them those of the United Kingdom and Italy. “True,” Dubi says. “He had connections with many people, including Western services. That was his assignment, while serving as Sadat’s special adviser. But the Mossad was the only one he got money from, and he can be termed a paid agent.”

Over the years Dubi and his managers, as is customary in the world of espionage, gave Marwan a number of code names, among them “Atmos,” “Pacety,” “The Angel,” “Hutel” and “Rashash.” Dubi always introduced himself as ‘Alex.” “One day, he asked me: ‘Is your name really Alex?’ No, I told him, that’s my cover name. He thanked me for my honesty.”

I asked Dubi if he could remember another interesting anecdote from his meetings with Marwan. “Yes,” he replied with a smile and, with the agility of an experienced gunman, pulled a small pistol out of his coat pocket and placed it on the table.

In one of their meetings, Marwan opened his suit jacket and Dubi saw a gun sticking out of his pocket. “What’s that gun? Do you want to shoot me?” Dubi asked with a smile that masked concern and apprehension. Marwan took out a small, loaded Smith & Wesson revolver from his pocket. Dubi tried to persuade him that it was dangerous to walk around London with a firearm and also against the law. Marwan was not convinced. “This revolver is always with me. Don’t worry. I’m careful,” Marwan said reassuringly, and besides that, he added, “Ana ma bathfatas” – “I don’t get searched.”

At their next meeting, Marwan took out a box. “I opened it and saw a Smith & Wesson. ‘It’s for you,’ he told me. I objected, but he refused to take it back. In order not argue with him or offend him, I agreed to take it. I sent the pistol to the Office, and Shmulik [Goren] allowed me to keep it.”

Dubi didn’t miss a single meeting with Marwan in the 28 years in which he was his handler, even after his retirement. At some of the meetings he was joined by Y., a radio technician and an experienced hand with technology. His job was to instruct Marwan in the operation of a wireless radio and other means of communication. The Mossad arranged for Marwan to receive a device in Cairo, but he never used it. Long afterward, when asked what had happened to the device, he replied: I threw it into the Nile. I thought it was too dangerous for me to have it in my possession or to use it.

Aside from Dubi, the person from the agency who spent the most time with Marwan was Zamir, who met with him six or seven times. Zamir explained that he asked to participate in meetings in order to get to know his ace agent better, even though he admitted that it was quite rare for a Mossad chief to come to meetings with his agents. “On the other hand,” Dubi emphasized, “the fact that the Mossad chief in person took the trouble to meet with him flattered Marwan and strengthened the ties with him.”

Zamir went so far as to say that he considered himself “Marwan’s friend.” Goren thinks otherwise – that Zamir wasn’t serious and also that it was in any case wrong for him to feel that way. “Agents, even the most important of them, are not friends and should not be friends of the Mossad head.”

Zamir retired from the Mossad in 1974. His successor, Yitzhak Hofi, also decided to meet with Marwan – once, in Dubi’s presence. Over the years, no few people in the Mossad coveted Dubi’s assignment and wanted to replace him. “Case officers envied me,” he says.

On three occasions Goren, Zamir, Hofi and Danny Yatom (the Mossad chief during the second half of the 1990s) tried to appoint a new handler for Marwan. And each time they failed. In one case, Marwan didn’t like the Iraqi origins of the intended agency replacement. In another case, a Mossad operative of Anglo-Saxon descent was sent to him, but he too was unable to win over the Egyptian agent.

The third attempt came in 1997, about a decade after Dubi had become a handler in retirement. It was the period of the Yehuda Gil episode – the Mossad case officer who for 20 years fabricated intelligence reports while claiming that his agent, a Syrian general, was willing to meet only with him. In Gil’s trial, on charges of espionage and fraud, in which he was convicted and sentenced to a five-year prison term, it turned out that he had in fact met with the Syrian, but had never succeeded in recruiting him and running him as an agent. The general viewed him as a friend and no more. Gil, who was ashamed to admit his failure, invented reports in which he set forth in great detail his conversations with the general. Senior figures in the Mossad and Military Intelligence bought the story and did not suspect Gil.

Against the background of that case, Mossad chief Yatom decided that case officers would not run agents for more than a few years. “We decided to change the method,” he explained. Accordingly, Dubi was instructed to meet with Marwan in a hotel in Palma de Mallorca. He was told that as soon as he entered the lobby he should ask Marwan to meet him for breakfast and not in his room, as usual. Marwan made a face but agreed. But while they were conversing, Marwan noticed a couple, a man and a woman, who were observing them with suspicious gazes. “They are listening to us,” Marwan said to Dubi, and the two went up to the room.

In the wake of this, because Marwan did not want to work with anyone else, Dubi informed him that their relationship had come to an end. “We embraced and parted as friends,” Dubi recalls. Nevertheless, he acceded to the Mossad’s request to maintain contact with Marwan for a certain period.

Still, in those years there was no longer an intense connection between Marwan and the Mossad. It had grown more lax already by the late 1970s. Marwan’s great importance lay in that decade, not only with the Yom Kippur War, but also after it, during the separation of forces agreements in Sinai and until the Israeli-Egyptian peace treaty in 1979. Afterward, his standing with Sadat declined and Marwan himself devoted increasing time to his own businesses – so his contribution diminished as well. The information he continued to provide about Egypt in an era of peace and ties in the Arab world was indeed important, but it was obvious to all concerned that it did not match the level and quality of the war era. Dubi, too, became involved in other matters over the years, between the meetings with Marwan, and even more so after the latter’s importance declined. During the period of the first Lebanon war, for example, he was sent as a case officer to reinforce Mossad’s operation in that neighboring country.

Battle for his good name

After the relations between Dubi and Marwan were mutually terminated, Dubi became angry. Not because he was longer meeting with the Egyptian, but out of concern for his safety.

The main reason for this, Dubi says, lay in the trickles and leaks from former Military Intelligence director Eli Zeira and his handful of followers, which led to Marwan’s name finally being made public. That happened in December 2002, when Marwan was first identified by name as an Israeli agent, in the Egyptian newspaper Al Ahram. The paper, it turns out, had approached Ahron Bregman, a political scientist of Israeli origin at King’s College, London, to confirm that the Egyptian who had spied for Israel, whom Bregman claimed was a double agent, was Marwan. The name was subsequently picked up by the international media and eventually, in the Israeli press.

Up until Marwan’s tragic death, in 2007, Dubi tried a number of times, in conversations with Zamir and other senior Mossad figures, to warn against Zeira’s actions. “Twice I wrote to the directorate that there was going to be a disaster. The first time they didn’t answer, and the second time a meeting was held in Tzomet in the presence of the Mossad chief, Meir Dagan. I was not at that meeting, but I saw its summation, in which it was decided to do nothing.”