China’s Relationship with Saudi Arabia Will Change the Global Economy

By Mishaal Al Gergawi November 07, 2017

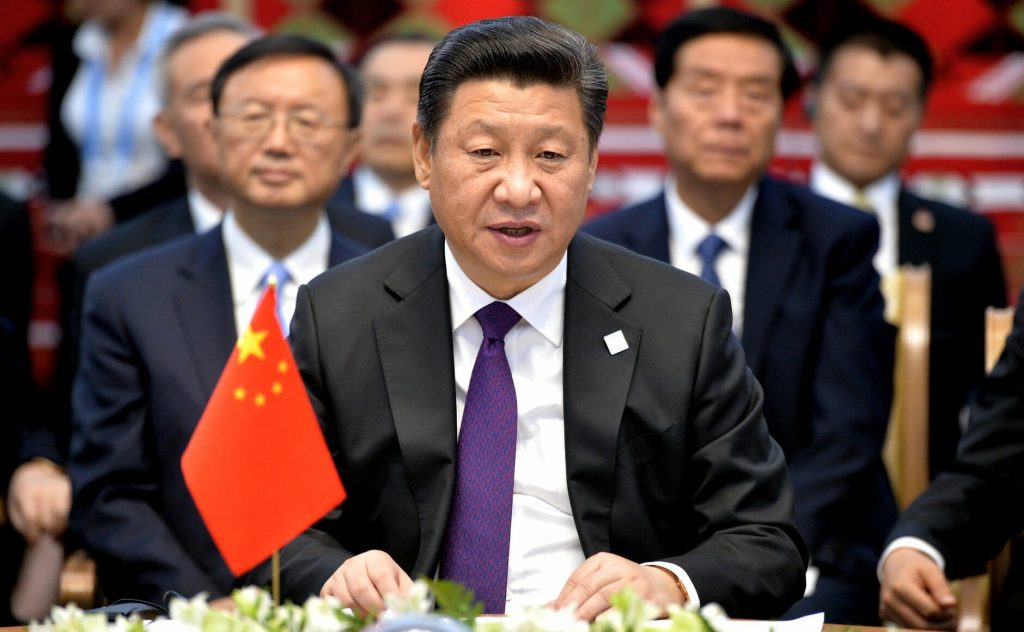

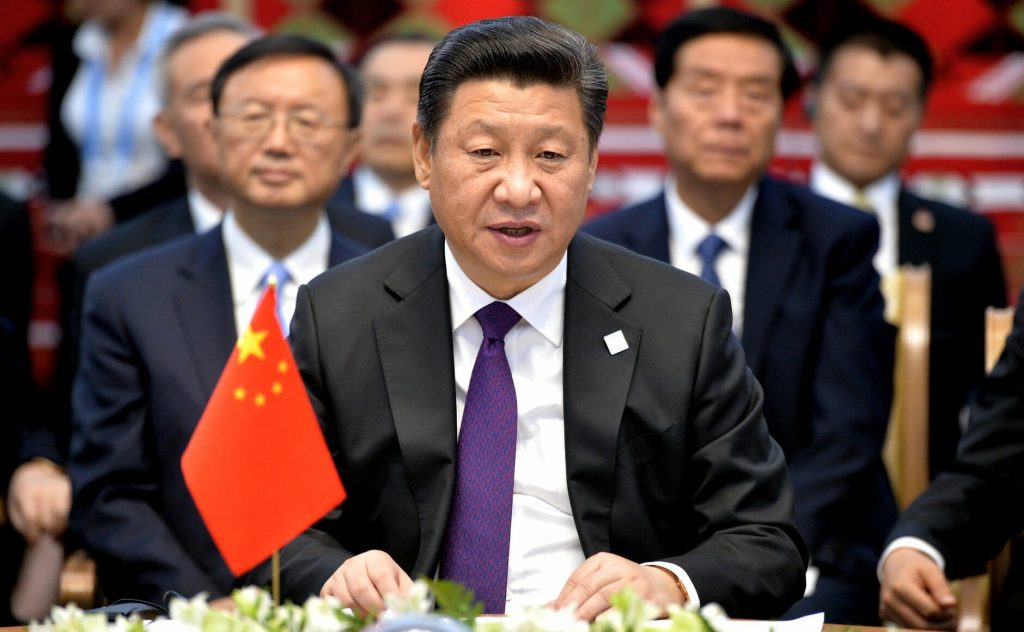

Chinese President Xi Jinping. President of Russia/Wikipedia Commons CC BY 4.0

Since the election of US President Donald Trump, relations between Saudi Arabia and the United States have seemingly returned to their halcyon days.

Saudi officials have been energized by Trump’s desire to roll back Iranian influence and his support for Saudi economic reforms, and they are enthusiastic about the two countries’ newfound unity of purpose.

But Saudi Arabia is not just being courted by the Trump administration. Without the pomp and circumstance of the Riyadh summit, where Trump addressed representatives from across the Muslim world earlier this year, the Chinese government is taking quiet steps to bring Saudi Arabia’s hydrocarbon reserves firmly into its orbit.

Through its ambitious Belt and Road Initiativeand a reported offer to invest in the kingdom’s state-owned oil company, Saudi Aramco, the Chinese are laying the groundwork for a profound economic shift in the Middle East and the world.

As it has grown over the last three decades, China has slowly become a much more important energy partner to Saudi Arabia and Gulf states.

Its emergence as an economic powerhouse has increasingly fueled its ambition to dictate the rules of the energy market: In recent years, it has scaled down its share of energy imports from OPEC members in favor of non-OPEC countries, primarily due to its preference to purchase oil and gas in yuan or the local currency of the exporter, rather than US dollars. China imports approximately one-quarter of its energy from Saudi Arabia, but Russia recently supplanted the kingdom as China’s top energy producer.

China’s fastidious control over its own currency is the first step towards upending the way oil is traded.

In return for conducting energy sales exclusively in dollars, the US agreed to sell Saudi Arabia advanced military equipment. Forged by US President Richard Nixon and Saudi King Faisal bin Abdulaziz Al Saud in 1973, the petrodollar system has wedded the greenback to the world’s most sought-after commodity.

One obvious reason China wants oil to be traded in yuan is to increase global demand for yuan-denominated assets. This would increase capital inflows and may eventually lead to the yuan being a plausible global alternative to the US dollar. Saudi Arabia is OPEC’s historic swing producer and price arbiter – if it agreed to conduct transactions in currencies other than the dollar, other OPEC producers would be forced to follow suit.

Beijing’s thinking is also influenced by geopolitical calculations. China’s return on investment in Saudi infrastructure could take decades, but Beijing would gain a valuable foothold in the Gulf and possibly persuade one of the world’s leading oil producers to upend the way oil is traded.

Moreover, Saudi Arabia and its Gulf allies, especially the United Arab Emirates, provide a valuable hub to Middle Eastern and African markets through their ports, airports, and global networks. This spring and summer, Beijing and Riyadh announced a number of deals in various sectors, including increased energy exports and a reported $20bn shared investment fund.

The equation is much more difficult for Saudi Arabia and the other oil-producing countries in the Gulf. On one hand, Saudi Arabia’s alliance with the US, however shaky, is the bedrock of regional security. On the other hand, growth in energy consumption will continue to be centered east of the kingdom, not west.

The Chinese have not given Saudi Arabia much time to consider its options. Chinese state-owned oil companies PetroChina and Sinopec have already expressed interest in a direct purchase of 5% of Saudi Aramco. This could prove to be a boon for Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman, who has been eager to achieve a $2trn valuation of Aramco in a highly anticipated initial public offering, which is currently scheduled for 2018.

Considering the depressed state of the oil market, investors may be hesitant to meet the targets for Aramco’s valuation that the Saudi leadership has laid out. A private Chinese placement could solve this dilemma – and allow Riyadh to delay the IPO in the hopes that oil prices will improve. While this investment may not explicitly require that Saudi Arabia agree to trade in yuan, it would give China leverage towards that goal. For Mohammed bin Salman, Chinese investment in Aramco could kick-start a new economic partnership with Beijing.

As part of its economic reform, Saudi Arabia’s ambitious Vision 2030 plan intends to raise foreign direct investment from 3.8% of GDP to 5.7%, or an additional $12bn per year.

It is a far safer bet that China would be able and willing to inject that type of money into Saudi Arabia than US private equity and hedge funds. The main reason for this is the difference in Chinese and Western time horizons when considering return on investment. While Western governments and companies have historically had appetite for infrastructure projects that offer a return on investment in a maximum of 30 to 40 years, the Chinese are playing a much longer game – in some cases investing in projects that break even in more than 100 years.

Saudi Arabia and China stand to gain from this geo-economic shift – but what about the US? For all its talk of remaking the US economy, the Trump administration must heed the changing economic currents. Given the depths of Beijing’s interest in Saudi Aramco, it seems many policy-makers in the Gulf and the West do not fully appreciate the geopolitical interests at stake. Aramco, formerly the Arabian-American Oil Company, will not rebrand itself – but it may effectively become “Archco”, the Arabian-Chinese Oil Company.

Asked how he went bankrupt, a character in Ernest Hemingway’s The Sun Also Rises responded: “Two ways. Gradually and then suddenly.”

It’s unlikely the petrodollar system will be fully replaced by an equivalent “petroyuan” system, but the dollar’s monopoly on major oil sales may loosen gradually – and then suddenly. That gradual process may have already begun.

A version of this article first appeared in Foreign Policy on October 26, 2017.

http://emerge85.io/articles/chinas-relationship-with-saudi-arabia-will-change-the-global-economy/

By Mishaal Al Gergawi November 07, 2017

Chinese President Xi Jinping. President of Russia/Wikipedia Commons CC BY 4.0

Since the election of US President Donald Trump, relations between Saudi Arabia and the United States have seemingly returned to their halcyon days.

Saudi officials have been energized by Trump’s desire to roll back Iranian influence and his support for Saudi economic reforms, and they are enthusiastic about the two countries’ newfound unity of purpose.

But Saudi Arabia is not just being courted by the Trump administration. Without the pomp and circumstance of the Riyadh summit, where Trump addressed representatives from across the Muslim world earlier this year, the Chinese government is taking quiet steps to bring Saudi Arabia’s hydrocarbon reserves firmly into its orbit.

Through its ambitious Belt and Road Initiativeand a reported offer to invest in the kingdom’s state-owned oil company, Saudi Aramco, the Chinese are laying the groundwork for a profound economic shift in the Middle East and the world.

As it has grown over the last three decades, China has slowly become a much more important energy partner to Saudi Arabia and Gulf states.

Its emergence as an economic powerhouse has increasingly fueled its ambition to dictate the rules of the energy market: In recent years, it has scaled down its share of energy imports from OPEC members in favor of non-OPEC countries, primarily due to its preference to purchase oil and gas in yuan or the local currency of the exporter, rather than US dollars. China imports approximately one-quarter of its energy from Saudi Arabia, but Russia recently supplanted the kingdom as China’s top energy producer.

China’s fastidious control over its own currency is the first step towards upending the way oil is traded.

In return for conducting energy sales exclusively in dollars, the US agreed to sell Saudi Arabia advanced military equipment. Forged by US President Richard Nixon and Saudi King Faisal bin Abdulaziz Al Saud in 1973, the petrodollar system has wedded the greenback to the world’s most sought-after commodity.

One obvious reason China wants oil to be traded in yuan is to increase global demand for yuan-denominated assets. This would increase capital inflows and may eventually lead to the yuan being a plausible global alternative to the US dollar. Saudi Arabia is OPEC’s historic swing producer and price arbiter – if it agreed to conduct transactions in currencies other than the dollar, other OPEC producers would be forced to follow suit.

Beijing’s thinking is also influenced by geopolitical calculations. China’s return on investment in Saudi infrastructure could take decades, but Beijing would gain a valuable foothold in the Gulf and possibly persuade one of the world’s leading oil producers to upend the way oil is traded.

Moreover, Saudi Arabia and its Gulf allies, especially the United Arab Emirates, provide a valuable hub to Middle Eastern and African markets through their ports, airports, and global networks. This spring and summer, Beijing and Riyadh announced a number of deals in various sectors, including increased energy exports and a reported $20bn shared investment fund.

The equation is much more difficult for Saudi Arabia and the other oil-producing countries in the Gulf. On one hand, Saudi Arabia’s alliance with the US, however shaky, is the bedrock of regional security. On the other hand, growth in energy consumption will continue to be centered east of the kingdom, not west.

The Chinese have not given Saudi Arabia much time to consider its options. Chinese state-owned oil companies PetroChina and Sinopec have already expressed interest in a direct purchase of 5% of Saudi Aramco. This could prove to be a boon for Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman, who has been eager to achieve a $2trn valuation of Aramco in a highly anticipated initial public offering, which is currently scheduled for 2018.

Considering the depressed state of the oil market, investors may be hesitant to meet the targets for Aramco’s valuation that the Saudi leadership has laid out. A private Chinese placement could solve this dilemma – and allow Riyadh to delay the IPO in the hopes that oil prices will improve. While this investment may not explicitly require that Saudi Arabia agree to trade in yuan, it would give China leverage towards that goal. For Mohammed bin Salman, Chinese investment in Aramco could kick-start a new economic partnership with Beijing.

As part of its economic reform, Saudi Arabia’s ambitious Vision 2030 plan intends to raise foreign direct investment from 3.8% of GDP to 5.7%, or an additional $12bn per year.

It is a far safer bet that China would be able and willing to inject that type of money into Saudi Arabia than US private equity and hedge funds. The main reason for this is the difference in Chinese and Western time horizons when considering return on investment. While Western governments and companies have historically had appetite for infrastructure projects that offer a return on investment in a maximum of 30 to 40 years, the Chinese are playing a much longer game – in some cases investing in projects that break even in more than 100 years.

Saudi Arabia and China stand to gain from this geo-economic shift – but what about the US? For all its talk of remaking the US economy, the Trump administration must heed the changing economic currents. Given the depths of Beijing’s interest in Saudi Aramco, it seems many policy-makers in the Gulf and the West do not fully appreciate the geopolitical interests at stake. Aramco, formerly the Arabian-American Oil Company, will not rebrand itself – but it may effectively become “Archco”, the Arabian-Chinese Oil Company.

Asked how he went bankrupt, a character in Ernest Hemingway’s The Sun Also Rises responded: “Two ways. Gradually and then suddenly.”

It’s unlikely the petrodollar system will be fully replaced by an equivalent “petroyuan” system, but the dollar’s monopoly on major oil sales may loosen gradually – and then suddenly. That gradual process may have already begun.

A version of this article first appeared in Foreign Policy on October 26, 2017.

http://emerge85.io/articles/chinas-relationship-with-saudi-arabia-will-change-the-global-economy/