The Chinese government has approved plans for a massive undersea surveillance network in both the East and South China Seas. Officially intended to primarily monitor environmental changes, state officials acknowledge the systems will have “national defense” applications, which could include tracking the movements of foreign submarines.

The plan includes a number of unspecified sensors on the ocean floor, connected via optical cables to a central processing and monitoring facility in Shanghai. The devices will be able to provide “real-time, high-definition, multiple interface, and three-dimensional observations,” according to state-run outlet CCTV.

“China is an ocean power; it should have done more in oceanic studies in the past,” Jian Zhimin, dean of the School of Marine and Earth Sciences at Tongji University in Shanghai, told CCTV. “An ocean power must be able to go to the high seas and go global.”

Ostensibly, the network forms a “laboratory” in which researchers can study climate change and maritime phenomena, Jian added. Additional reports suggested that this equipment would be calibrated to gather chemical, biological, and geological data. But the national security implications are hard to miss.

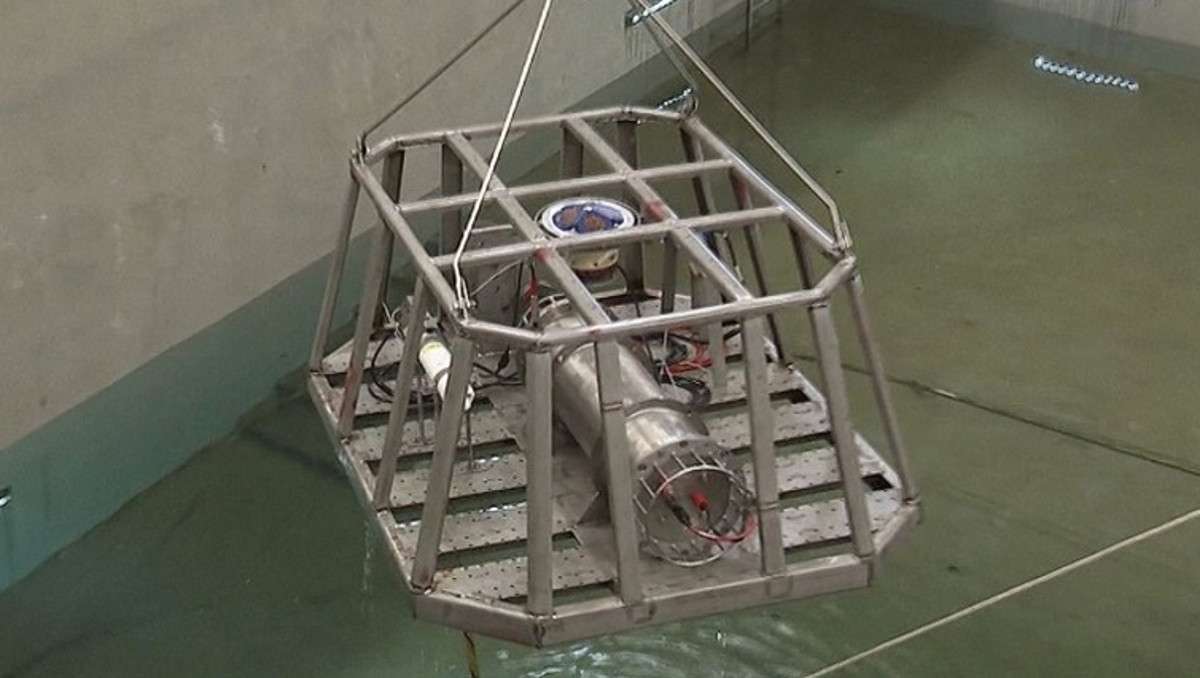

CCTV

A prototype of one of the sensors for China's new monitoring underea system.

The underwater system could be useful for “other sectors, such as mining, mapping or ocean rights protection, and national defense in addition to scientific research,” Zhou Huaiyang, a professor in Tongji’s School of Marine and Earth Sciences, explained to CCTV. “We hope different governmental departments can work together to work out stricter regulations and measures on the protection of these undersea facilities, so as to ensure the long-term operation of this system.”

It is possible that Zhou’s reference to “national defense” referred to the preservation, exploration, and exploitation of natural resources for China’s benefit. The East and South China Seas may contain untapped reserves of oil, natural gas, and valuable minerals, as well as just being important sources of fish and other edible marine animals.

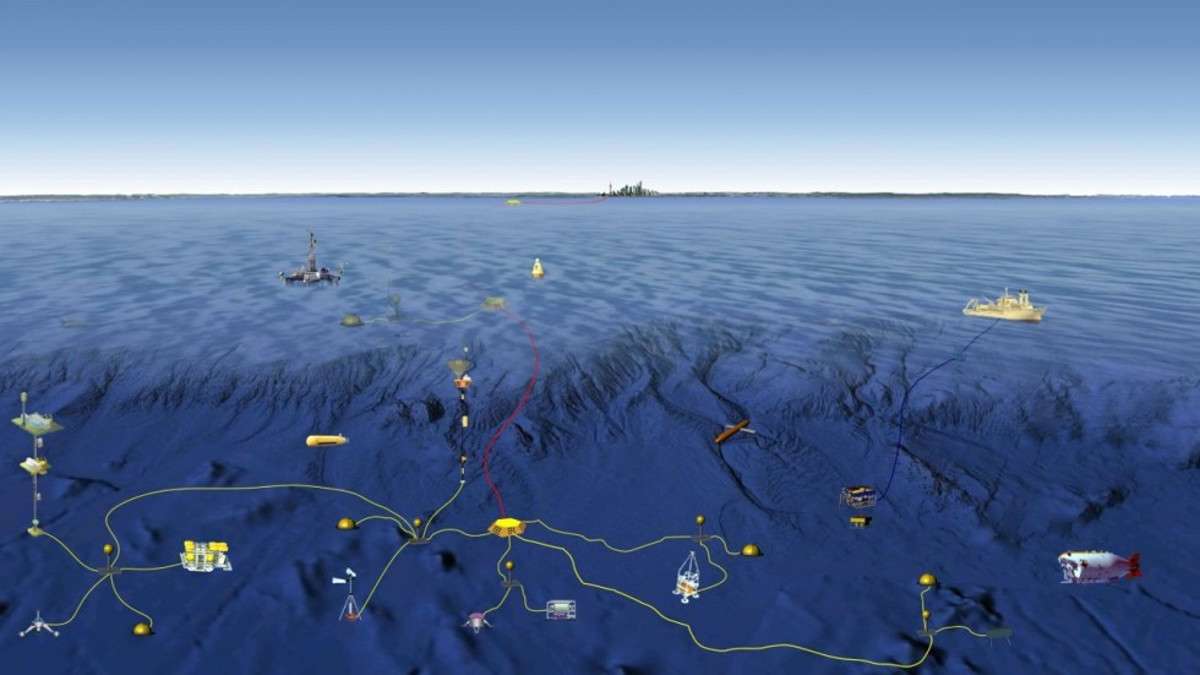

Chinese government handout via South China Morning Post

An artist's conception of the undersea network.

However, it seems much more likely the network’s defensive function would have to do with monitoring foreign military movements, especially of submarines. Earlier in May 2017, IHS Jane’s Defence Weekly reported that the state-owned China State Shipbuilding Corporation had presented details of a massive “Underwater Great Wall Project” for the People’s Army Liberation Navy (PLAN) during a public exhibition the previous year. That proposal sounds extremely similar to the one CCTV announced in size and scope if not necessarily stated function.

During the Cold War, the United States maintained a similar system to guard itself against Soviet submarines, known as the Sound Surveillance System, or SOSUS, which employed groups of ultra-sensitive hydrophone listening devices along the seabed . As a result of espionage, the U.S. Navy was ultimately forces to employ a combination of fixed sensor arrays, surface ships towing sonar, and processing stations ashore, known as the Integrated Undersea Surveillance System (IUSS). But even decades after the collapse of the Soviet Union, elements of the system remain in use or available in a crisis.

Chinese government handout via South China Morning Post

A model of the undersea network.

A similar Chinese system in the East and south China Seas would be essential for Beijing to enforce its claim to almost in their entirety of both bodies of water. Nearly every one of the country’s neighbors, as well as major international maritime nations, disputes China’s dominion over these regions. Many, such as the United States, actively challenge the country’s position by sailing through or flying over the area.

By 2015, “China demonstrated a willingness to tolerate higher levels of tension in the pursuit of its interests, especially in pursuit of its territorial claims in the East and South China Sea; however, China still seeks to avoid direct and explicit conflict with the United States,” the Pentagon noted in an annual public report to Congress on Chinese military developments. “In the near-term, China is using coercive tactics short of armed conflict, such as the use of law enforcement vessels to enforce maritime claims, to advance their interests in ways that are calculated to fall below the threshold of provoking conflict.”

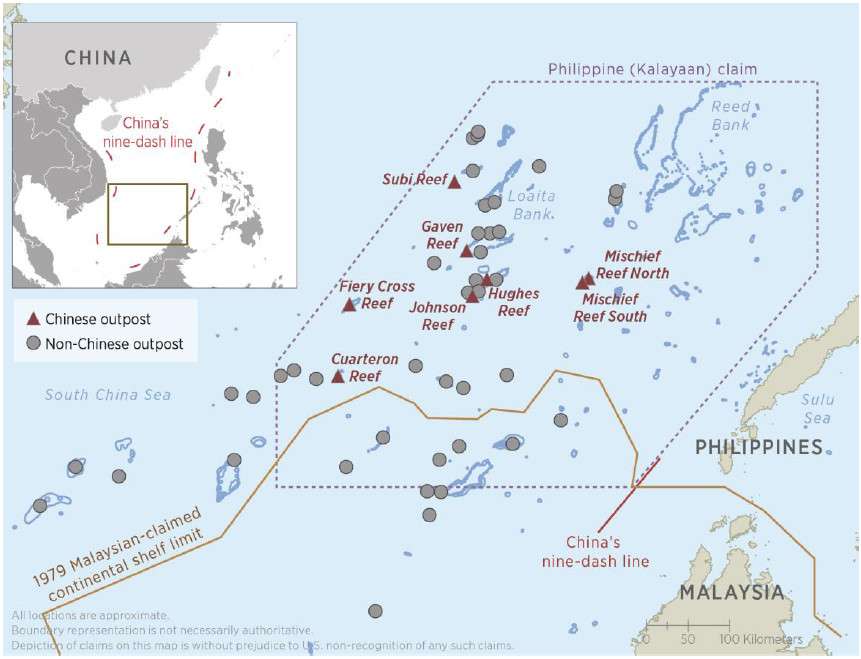

DOD

A map of Chinese and foreign outposts in the South China Sea.

Most visibly, since 2014, the Chinese government has been actively turning at least eight previously uninhabitable reefs and shoals into man-made islands able to support military outposts. The operations at locations such as Fiery Cross, Mischief and Subi Reefs in the South China Sea have airstrips able to support fighter jets and heavier aircraft, apparent radars and launch sites that could accommodate surface-to-air and anti-ship missiles for local defense, and other facilities. In March 2017, the Center for Strategic and International Studies said that commercial satellite imagery suggested these military sites were close to fully operational. The Washington, D.C. think tank created an interactive map to go along with their report, showing Chinese aircraft, missiles, and radars provide extensive coverage throughout the South China Sea.

For China, these bases are important fixed “territory” it can point to when defending its claims and as part of legal arguments it makes in front of international bodies. Similarly, it has enacted an Air Defense Identification Zone (ADIZ) over the East Sea as another method of attempting to enforce its position. Within this zone, the country argues it can restrict foreign military movements and even dictate civilian flight paths, with any organization needing to coordinate air travel with Chinese officials. There are reports that China may be considering declaring a similar zone over the whole of the South China Sea, something its new islands could help monitor. At sea, Chinese authorities have made similar pronouncements about their control over international waters in both the South China and East Seas.

In both regions, to reinforce the country’s claims of absolute ownership, Chinese aircraft and warships have repeatedly harassed foreign civilian and military activities. The United States has responded with regular aerial and naval patrols to challenge this assertion. And though both countries might want to avoid an actual skirmish, tensions have often run high during these missions. Chinese fighter jets routinely buzz American patrol and surveillance aircraft. In May 2017, two People’s Liberation Army Air Force (PLAAF) fighters performed “unsafe and unprofessional” maneuvers near a WC-135 Constant Phoenix spy plane, which collects air samples looking for evidence of nuclear tests, in international air space over the South China Sea, according to the U.S. Navy.

The China’s navy, various other maritime security forces, and the People's Armed Forces Maritime Militia – popularly known as “Little Blue Men” – all similarly shadow American warships as they move through the area during what the Pentagon pointedly refers to as “Freedom of Navigation Operations” (FONOPS). Rarely do the two sides ever truly meet. In a rare incident in May 2016, PLAAF jets scrambled from the airstrip on Fiery Cross Reef in response to the Arleigh Burke-class destroyer USS William P. Lawrence’s trip through the area. More flagrantly, on Dec. 15, 2016, a Chinese ship snatched a U.S. Navy underwater glider, a type of drone the service uses for underwater mapping and research activities, right out of the water and sailed away. Within a week, China had returned the Slocum glider without any real explanation of why they seized the unclassified vehicle in the first place.

But what the Chinese military hasn’t been able to do is challenge the U.S. Navy’s submarines, or those from other developed nations that patrol the East and South China seas, such as Japan and Australia. Able to operate for protracted periods under the waves, subs have an innate deterrent capability and could easily be a hidden threat to China’s man-made naval outposts during a crisis. The undersea vessels could also spy on those bases without Chinese forces being able to necessarily respond.

AP

A Chinese warship launches anti-submarine rockets during an exercise in 2005.

In February 2017, Chinese state media announced planned changes to the country’s maritime safety statute, which would require submarines to sail on the surface with a national flag displayed when passing through regions such as the South China Sea, while reporting to Chinese maritime security organizations. Chinese officials expected the changes to take effect in 2020. "As a sovereign State and the biggest coastal State in, for example, the South China Sea, China is entitled to adjust its maritime laws as needed, which will also promote peace and stable development in the waters," Wang Xiaopeng, a maritime expert from the Chinese Academy of Social Sciences, told the state-operated newspaper Global Times. But, in addition to violating the most basic spirit of international maritime law, this would be difficult if not impossible for China to enforce at present.

Though the PLAN has spent considerable effort in improving its own “silent service,” submarines remains a relatively small portion of the country’s naval arm. As of 2016, China had approximately 56 attack and guided missile submarines, but a significant number of those are old Cold War designs or smaller coastal defense types, according to that year’s edition of The International Institute for Strategic Studies’ The Military Balance. The United States operates a similarly sized fleet, but one entirely comprised of long-range, ocean-going, nuclear-powered vessels. In addition, the U.S. military boasts more than twice as many nuclear-armed ballistic missile subs, not including four doing duty as cruise-missile boats. So, instead, the Chinese military would have to devote significant surface ships and aircraft just to hunt for foreign subs violating its new regulations.

SteKrueBe via Wikimedia

A Chinese Song-class submarine.

An underwater surveillance net able to detect and track submarines traveling in and out of an area could dramatically change the calculus for world navies operating in the East and South China Seas, as well as potentially improving China’s negotiating position. The country has been undeterred by unfavorable determinations on its claims from international tribunals, insisting that it has the right to settle any disagreements directly with the affected parties.

Of course the new capability won’t come cheap. Official estimates are that the underwater project will cost approximately $2 billion Yuan – $300 million at the official, likely undervalued exchange rate – and take at least five years to complete. It’s not clear whether or not this will be the final total for the complete network that covers all of the East Sea and South China Sea, or just one initial portion covering a specific area.

What is clear is that China seems intent on challenging the ability of foreign navies to sail through bodies of water it considers to be part of its national territory, even under the surface.

http://www.thedrive.com/the-war-zon...environmental-sensor-net-could-track-u-s-subs